Miklos Legrady ArtBlog 2019

I'm grateful to the New Art Examiner for offering me an op-ed column of my own, on any subject of interest. if you want notice when a new article appears, subscribe at legrady@me.com

<-- back to January - February

MARCH

21-Our Creative Unconscious

Miklos Legrady, 16" x 20" - 40.64cm x 50.8cm, acrylic on canvas, 2014

We've read how some wait for inspiration before they start to paint, and how they’re advised to start first, inspiration comes later. Interestingly enough the last two months I found myself unwilling to paint, although I'm writing a lot. I have a number of paintings waiting to be finished or new ones to start, yet whenever I move in that direction all motivation disappears, as if I’m pushed away from the medium. During that same time I've written some 20 blog pieces, 3 published, and a review with outstanding photography, also published.

My visual output consists of some 1000+ finished paintings over ten years; that's about two paintings a week over a decade. But the production does seem to occur in waves, with empty periods of weeks or even months, followed by constant and enthusiastic production.

I think about our brain cells, those neurons where painting begins, they’re wet, 60% water, and firing off electric and chemical impulses, it's complicated. Studies on creativity document how one must put all of one's energy to solve a problem, then let it go, do something else, engage in other work, and eventually when least expecting it, the idea will drop into one's head. There's Archimedes' famous Eureka moment, while more recently a math wizard was stepping off a bus when the proverbial light bulb above his head lit up with the correct answer to a complex equation.

All documentation on creativity agree on the pause, the rest between effort and conclusion, where the problem descends to the depths of the inner mind, the unconscious behind our blind spot. There it's chewed over until the best solution is found and pops up in consciousness.

There's may be competition in the brain between the visual cortex and the language areas, which include Broca's and Wernicke's areas and the frontal cortex. Duchamp made a major contribution to the epistemology of art when he made painting intellectual and found himself unable to paint. He had discovered the boundaries of visual art, the distinction between intellectual and visual language. Now my mind seems focused on intellectual projects, leaving no energy for visual production. It’s also possible that the waves of rest and effort intersect off-phase, so that when painting rests then writing surges, and when writing gets exhausted and takes a break, then painting reawakens.

Then there’s always the artist’s fear, the possibility of talent used up, exhausted, over and done with, the effort made and that’s the end. Whenever one has a gift there’s always the thought that to everything there’s a season and seasons change. We find comfort knowing that creativity does occupy a special place which could exempt it from the classification of temporary practices. Creativity is not a trend, nor a media, but a function. It is hard-wired and vital to mental health.

March 02, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

22-Why art is wonderful

February 3, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

23-#CulturalAppreciation

Fashion designer Pedram Karimi is a young bronze-skinned Iranian immigrant, who says his message is inclusive love and nothing else. In 2018, he was invited to stage costumes on the theme of stereotypes for the Art Gallery of Ontario’s annual Massive Party. His oriental styles were later accused of racism by a writer in New York, paid by the CBC, who saw a photograph she was sent. The feet on the ground were the Asian-Canadian members of the art community, who later wrote on the AGO’s Facebook page that they saw no insult, no racism.

As artists we refute this; we will not reinforce the oppressor-oppressed binary through which social-justice advocates see the world. We're not slaves to the past, and we can create a better future. Say no to perpetuation. As artists we can + we need to change the world.

Iranian-born Pedram Karimi and Hungarian-born Miklos Legrady created this logo and coined #CulturalAppreciation to prevent triggering situations, by posting that the artist is using cultural symbols with care and respect

Available to all copyright free, including the A.G.O, our bespoke term sees artists respecting other cultures in their work. A trigger warning notice, #CulturalAppreciation protects cultural freedom and allows complex civilization, says that an artist is using symbols with respect and without insult. When that meme is posted it's a sign that intentions do make a difference.

March 4, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

24-Sweden's Lucky Person

This experiment in sociology has nothing to do with art, as in the art of conversation, the art of cuisine, or with the Renaissance’s Borgia family, the art of poisoning your friends and enemies. Art is the direct opposite of doing nothing. Hiring someone, while it can be an art, mostly isn't. More proof the art world has been taken over by charlatans.

Two years ago Canada's Sobey Prize was awarded to a length of metal fence rented from Home Hardware. Roger Scrutton writes in The Great Swindle "So powerful is the impetus towards the collective fake that it is now an effective requirement of finalists for the Turner Prize in Britain to produce something that nobody would think was art unless they were told it was”. The dominance of the fake suggests a decadence in our time as bad as ancient Rome.

Roger Scrutton says "Faking depends on a measure of complicity between the perpetrator and the victim, who together conspire to believe what they don’t believe and to feel what they are incapable of feeling… Anyone can lie. One need only have the requisite intention — in other words, to say something with the intention to deceive. Faking, by contrast, is an achievement. To fake things you have to take people in, yourself included. In an important sense, therefore, faking is not something that can be intended, even though it comes about through intentional actions. The liar can pretend to be shocked when his lies are exposed, but his pretence is merely a continuation of his lying strategy. The fake really is shocked when he is exposed, since he had created around himself a community of trust, of which he himself was a member. Understanding this phenomenon is, it seems to me, integral to understanding how a high culture works, and how it can become corrupted."

Roger Scrutton A Cult of Fakery has taken over what’s left of high culture.

March 10, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

25-Abrahamic Religions

That is so true. Orthodox behavior really looks delusional... But then think of a God who needed you to kill his own son on a crucifix, to expiate the sins of a people who sinned because God made them that way. A God who needs blood sacrifice!!! That is the God of the Arabs, Jews, and Christians, the 3 Ambrahamic religions.

This God acts without justice, if you sin he kills your extended family along with your goats and sheep and camels, yet insists on being called all-just. A God who send the 7 plagues of the Apocalypse yet calls himself all-loving. There's only one conclusion. This God needs to be locked up, in jail, then given the best psychiatric treatment available, for He's a homicidal killer.

There's another view, that God represents the highest level of maturity in the collective consciousness of humanity. In that case this God is delusional, lives in denial, and that is the mindset of the people of Abrahamic religions. Just like Trump, a lot of people are living in denial of their bad side, and so they give it full reign.

It is because the fundamentalists, Arab, Jew, or Christian, so believe in their own essential goodness that they can't imagine they'd ever do anything wrong, so allow themselves to do the worst evil. Carl Jung really puts God on the psychiatrist's couch in his "Answer to Job", one of the best analyses of Yaweh, from which the above is drawn.

These situations have happened before, if we don't wipe ourselves out we'll improve from the experience.

March 11, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

26- Not Venini, Now Rioda

In 1921 Paolo Venini, Milanese lawyer, and Giacomo Cappellin, Venetian antique dealer, founded Cappellin Venini & C. They purchased the recently closed Murano glass factory of Andrea Rioda, hired the former firm's glassblowers, and retained Rioda himself as technical director, with the painter Vittorio Zecchin as artistic director. Now Rioda’s efforts and talent, his heritage and reputation would go on to enrich two clever businessmen.

Rioda died soon after selling his firm and engaging as technical director, most likely of heartbreak at losing his life’s work and ending up as a hired hand at what has been his own company. Andrea Rioda had owned his firm and was himself an artist designing and making glass; a number of extant glassworks bear his name. After his death, many of the glassblowers left the Venini firm and founded their own glassmaking company titled "Successors of Andrea Rioda”.

The irony consists of a Wikipedia page for Paolo Venini, and both Murano and Venini glass, but Andrea Rioda has no Wiki entry of his own, he only appears on Venini’s page, as if by buying his company Venini ate Rioda and digested him. Rioda’s possible death by disappointment is the mythical tale of the unappreciated neglected artist and yet we today can give him a well-deserved respect when we see that Murano glass is filed under Venini. Just as Duchamp’s urinal, called The Fountain, was not by him but by artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, so Murano and Venini works should be recognized as Andrea Rioda glass.

March 14, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

27-Canadian art mag says painting's bad.

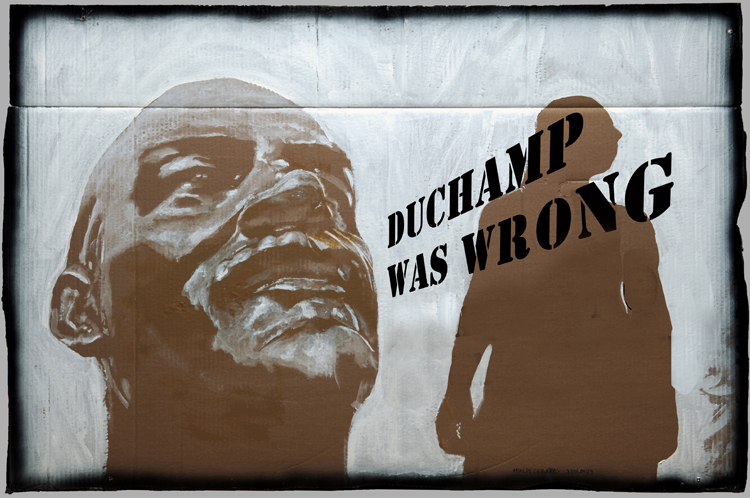

Miklos Legrady, 36" x 55" - 91.44cm x 139.74cm, acrylic on cardboard, January 11, 2016

Canadian Art magazine plans to publish a 2019 Fall issue undoing painting. They are calling for essays against the medium, the tone suggested by an intellectual who seems hostile yet confused by the medium.

Fall 2019: Undoing Painting - Call for submissions (sic).

Another painting issue?! Here, we present painting as an issue. Still one of the most marketable art forms out there—and therefore one of the most canonized and institutionalized—painting is a flashpoint for how we think about power, commerce and class in the art world. But what does a painting-focused view of contemporary art leave out—and include? Equally relevant—whom does it leave out and include? Does the market-bound nature of painting restrict its ability to critique? How are painting practices gravitating towards the interdisciplinary and installation-based? Are material-specific practices still valid—and does asking this question elide, say, Indigenous art communities, who have been working with paint across generations? What are all the things that painting can do that remain under-discussed? And how have painting’s histories been received and (mis)understood?

Undoing this call.

Unpacking this call unwraps a bias that strays from the truth, like someone studying humanity by doing their research on death row; the hostility in this call as well as an ignorance of the nature of painting become evident. The main point of the call is at the beginning, the editor using trigger words to position painting as a seductive but politically-incorrect elitist commodity.

Painting to this editor is about power, commerce and class in the art world. In the real world, this has nothing to do with painting or painters, few artists have money and network behind them, even among the charlatans who manage to play the system. (In this art ecology the critic could be a parasite on the painter.) The majority of painters in the art community are not driven by market values, are neither rich nor famous. They work with paint as a non-verbal language because they're driven by vision and inspiration.

But then we're also told a painting-focused view of art leaves things out. Not just things but people are left out: painting is unfair to other artists (and things). We're also told painting practices are now gravitating towards performance and installation, leaving open the cause for these supposed better options. The language of the call is disingenuously innocent, while cleverly worded with hostile signifiers, perhaps a hint of the tone expected of our article, following this editor's bias and their lack of familiarity with the subject discussed.

Painting is bad, unless it’s the kind of painting done for centuries by First Nations people. That kind of painting is good. This failure of logic suggests a reverse racism that jumps to the wrong side of a horse instead of landing in the saddle.

Painting is a non-verbal visual language with its own syntax and grammar. Painting was already sophisticated in a preliterate past, and even in post literate culture a healthy picture is still worth a thousand words. To be more accurate, the visual language of painting conveys data that words cannot express, as do music or dance.

The creative experience of painting operates as much from unconscious processes and requires enormous drive and effort, and love of making; those who claim otherwise and act accordingly are not painters but opportunists. If the cultural canon embodies an attitude of epistemic arrogance, the epistemic value of dissent will be difficult to realize.

Ironically, it is precisely then that dissent is most often needed.

If you believe the Fall issue should be led by someone who respects painting, email Canadian Art to let them know - info@canadianart.ca

March 23, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

28-Most counter-aesthetic

Miklos Legrady, 22" x 28" - 55.88cm x 71.12cm, acrylic on cardboard, Dec. 06, 2015

Postmodernism entered the university asking for the most counter-aesthetic art. Will anyone dare trade their tradition in exchange for intellectual heights? Until postmodernism, tradition meant aesthetics and beauty, non-verbal languages like dance, music, visual art.

In the 1960s Dada and Duchamp were given a second life in America, through John Cage, Robert Motherwell and a few other Socal artists and professors. The movement consisting of rejecting tradition, it allowed artists to ignore the exam and get past the gate. A lack of skill was said to signal a deeper understanding of art by doing the opposite, a strategy most clever.

Lacking skill, one stays a beginner. A naïve style was seen as a rejection of virtuosity, of unlearning colonial attitude. It was a clever way to make art, skipping the years of study that lead to mastery. One has only to declare oneself an artist, and one was. In fact that was the manifesto of Toronto’s General Idea, their art based on camp and clever repartee. "We wanted to be famous young artists, and we said we were famous young artists, and so we became famous young artists."

Few saw the dead canary; General Idea were good designers. They paired cleverness and art fashion with some excellent design, yet purposefully superficial, they blurred the line. Posing became art, like the fox invited into the chicken coop. Once you reject tradition it opens a lot of doors to academics who like art but lack talent. As any amount of mastery requires effort, those who skipped the work could focus on marketing.

Psychology speaks of art therapy, based on an aesthetic of self-expression. Anthropology also speaks of the art instinct of aesthetics. Aesthetic taste, argues Denis Dutton, is an evolutionary trait, and is shaped by natural selection. It's not, as most contemporary art criticism and academic theory would have it, "socially constructed". The human appreciation for art is innate, and certain artistic values carry across cultures. It seems an aesthetic perception ensured the survival of the perceiver’s genes. Dutton argues, with forceful logic and hard evidence, that art criticism needs to be premised on an understanding of evolution, not on abstract "theory".

If art is specific, if it is not "anything you can get away with", if art also functions as therapy, then we have to question the art world's attitude since the 1920s, of the counter-aesthetic, of doing the opposite of art, of making art into "a pharmaceutical product for idiots".Picabia One can trace the influence of this art for idiots from post-modernism to the post-truth era.

Those who still think that art is to piss on, should now leave the field for people with higher standards.

March 26, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

29-Curators

33" x 47" - 83.82cm x 119.38cm, acrylic on cardboard, January 26, 2016.

The Chinese text; "The sunshine of Mao Zedong Thought illuminates the path of the proletarian revolution".

I see them as delusional. That’s bad, I know. Since I write about curators, it’s no wonder I’m unpopular with that crowd. A Canadian curator is more like one Aspen tree among a forest of them, linked by their root network, so many different trees rising from an academic ground yet their ideology is near identical. Whereas I write that postmodernism is a mistake, and that’s not just my opinion, that’s science, and also a growing number of cultural workers commenting on "the deplorable state of contemporary art". Postmodernism is deliberately anti-aesthetic. Meanwhile the science of psychology says art therapy is all about aesthetics, which is vital for mental health. What’s the effect of a counter-aesthetic art? We know when Duchamp discarded aesthetics he stopped painting, it was like a broken leg he said.

Postmodernism shades our curators, those who grew up in the last four decades and went with the flow, as Marshal McLuhan said that art is anything you can get away with. Now it’s important to note that in the 1960s art moved from the Cedar Tavern to the seminar room. To see how this changed the art paradigm we recall that academia is primarily intellectual and verbal, whereas at least five modalities of art are non-verbal. Body language including dance; acoustic language including music; visual language; the language of feelings; and the language of sensations. Only one faculty is verbal, the art of writing, and only here does the intellect rule. As we make art conceptual, intellectual, we make it shallow, by cutting away the non-verbal languages it depends on. Intellectual knowledge has the blind spot of assuming that what one knows is adequate, whereas we likely see through a glass darkly.

Conceptual, intellectual, and anti-aesthetic are today’s dominant trend; our curators have become gatekeepers enforcing the homogeneity of a status quo that’s not viable. If you’re an art school graduate you’re neither an artist nor a curator; you’re a high priest in an esoteric cult as far removed from art as homeopathy is from real medicine.

That's why artists question a curatorial power that both controls their lives and defines the art of our time. It’s a disputed power because curators are not artists. They’re outsiders, intellectuals interested in art. As students they learn current trends and biases, today’s being that the idea is the most important aspect of art. And these newly minted students will approve and support the mould they were cast in.

As the art world moved from the Cedar Tavern to the seminar room, thinking about art became more important than the non-verbal languages. The academic system encourages communication, writing, and administrative agreement. But for artists, Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours to mastery takes an extreme effort and commitment. It means literally hours entangled in material processes that impose reality checks until one achieves mastery of the field. In academia, we’re producing tens of thousands whose formative studies raised them to think and talk about art but with little practice, lacking the reality check between ideas and accomplishments.

This critique of curators equally critiques the status quo and the cultural cannon. It’s not just curators of course. It’s only recently that we have a scientific perspective of art, revealing it’s vital role in culture, whereas we’ve lived through 40 years of art being anything you can get away with. Forty years ago an earnest experiment began, of rebelling against tradition. How important such traditions actually were would not become obvious till much later. Roger Scruton now writes of fake art and artists; "High culture is being corrupted by a culture of fakes".

Art is a new religion yet already needs a Martin Luther.

March 29, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

APRIL

30-Akimbo: censorship and corruption in Canadian art

32.5" x 33" - 82.55cm x 83.82cm, acrylic on cardboard, November 28, 2015

Akimbo is a monopoly, the only Canadian art advertising network. It reaches from coast to coast, anyone can book large or small email ads which are sent out daily. Akimbo has an extended mailing list of subscribers, including most Canadian art schools, museums and galleries, as well as countless artists, writers, and editors. Akimbo's founder Kim Fullerton is now extending the akimbo ad agency into a cultural media working with writers and curatorial critiques.

Interestingly enough, Ms. Fullerton also censors articles she does not like, refusing ads to writers she disagrees with. Because she runs a monopoly in the Canadian art world, her editing means silencing voices and diversity, censoring their ideas according to Kim Fullerton's beliefs of what the Canadian art community should see and hear.

Disclosure; I’m one of those censored (see below). Ads for my articles, reviews, and exhibitions are refused. My experience was so arbitrary I suspect I’m not alone. Until last year’s conflict Kim and I were friendly acquaintances, I once visited her farm near King City. When she texted refusing to accept ads from me, I was surprised; she then ignored my emails s to connect, discuss, listen, explain and compromise. An open mind is good since we can all learn something. Then I thought she may be close friends with those I critique and really felt insulted at reading a critical review; as if writing such was bad manners in the Canadian art world... it certainly rarely happens, if at all. Or else Fullerton identifies with postmodernism and took that critique to heart. Both position are unethical but in the heat of passion one doesn’t think of that.

My writing paints a picture of what’s out there, I’m not making it up. Duchamp said the readymades were never art. Stuff like that upsets people and threatens jobs and legacies. I try to be witty… when people make bad art, it’s malpractice.

Ms. Fullerton in effect controls the Canadian cultural canon according to her personal bias, and as Toronto editor of Chicago's New Art Gazette, I now publish my work outside Canada, in the U.S. and England. We might well suppose there are top tier Canadian curators and directors who collude to repress ideas that threaten their jobs and ideology. While all Canadian art charter calls for diversity, there is obviously little diversity in such an approach. Understanding this phenomenon is, it seems to me, integral to understanding how a high culture works, and how it can become corrupted.

In 1947 statistician R.A. Fischer was invited to give a series of talks on BBC radio about the nature of science and scientific investigation, his words are just as relevant to the arts today. “A scientific career is peculiar in some ways. Its reason d’être is the increase in natural knowledge and on occasion an increase in natural knowledge does occur. But this is tactless and feelings are hurt.

For in some small degree it is inevitable that views previously expounded are shown to be either obsolete or false. Most people, I think, can recognize this and take it in good part if what they have been teaching for ten years or so needs a little revision but some will undoubtedly take it hard, as a blow to their amour propre, or even an invasion of the territory they have come to think of as exclusively their own, and they must react with the same ferocity as animals (whose territory is invaded). I do not think anything can be done about it… but we should be warned and even advised that when one has a jewel to offer for the enrichment of mankind, some people will certainly wish to discredit that person and shred them to bits.” Especially if their job and legacy were at stake.

What is this legacy? For the last 40 years the art world explored one of the most esoteric and sophisticated methods of thinking about art; that of denying it. Postmodernism is anti-aesthetic, shocking, contrary, it is non-art. And so, with non-art we have no art.

Yet, in the arts, aesthetics is a system of value judgments, of comparisons and evaluations that provide statistical data by which we organize sensations pouring in from without, and reactions emerging from within. Aesthetics plays a meaningful role in a linguistic theory of intelligence, because as a set of judgments it covers the entire spectrum from attraction to repulsion, from dark to light, and similar sensory dualities. Art and aesthetics are not simply cheesecake for the mind nor are they simply decorative. They are an evolutionary adaptation of the highest order in creating and processing subtleties of knowledge and complexities of thought.

Those who promoted what seemed at the time the most exciting period of art will not be pleased to discover they were off on a wild goose chase, and that when all is said and done, they themselves proved that they were wrong. No one wants to accept that their legacy was a mistake so they will try to silence evidence, will try to protect their life’s work.

Danielle S. McLaughlin of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association said that when we can no longer explore and express ideas that are troubling and even transgressive, we are limited to approved doses of information in community-sanctioned packets. Such self-service is harmful to the community; this controlled approval and official sanction is open to corruption, simply because people defends their position against change, yet change is the only constant in life.

April 3, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

Here are the two articles director Fullerton objected to under a rubric of ad hominem. That means an attack on a person's character to avoid dealing with valid arguments; these article are just the opposite, they present valid arguments. Readers can judge for themselves.

1-#CulturalAppreciation.

2-Luis Jacob Ten Years Later

31-After Postmodernism

"After Postmodernism" is a book project based on notes, essays, and published articles I've written over the years that I've been fascinated with this movement.

This research sourced historical documents and current practices, until a pattern emerged suggesting that postmodern influence was in decline and a new movement would inevitably rise from the ashes. The premise of this book is that new movement will be a correction of the previous, and these changes occur as we learn about what was swept under the rug.

Derrida’s method of deconstruction was to look past the irony and ambiguity to the layer that genuinely threatens to collapse that system. Recently a top-tier curator wrote that no one knows what art is anymore, which suggests the contradictions within postmodern theory do threaten to collapse that system. If no one knows what art is, then either fine art is ineffective and meaningless, or else today’s practice is no longer art but malpractice; every other profession knows what they are doing.

We know that an entire profession can go off the rails in light of the 2008 Global banking collapse based on sub-prime loans. If bankers can go bonkers then artists as a group are certainly not immune to errors.

Mr. Jean Clair, director of the Musée Picasso in Paris, and in later years a fierce critic of l’art contemporain, was a major interpreter of the work of Marcel Duchamp. He organized the Duchamp retrospective which was the inaugural exhibition at the Centre George Pompidou – and he wrote a catalogue raisonné of Duchamp’s work… Recently he has come to hold Duchamp in large measure responsible for what he regards as the deplorable condition of contemporary art. Art historian and critic Barbara Rose also writes that what was done in Duchamp’s name was responsible for some of the most inane, most vulgar non-art still being produced by ignorant and lazy artists whose thinking stops with the idea of putting a found object in a museum.

Art has always contained the illogical within it’s purview. Postmodernism on the other hand fails to contain it; it accepts the illogical as valid equivalence and elevates it to a ruling principle. This denial of logic fails every reality tests; rejection of the sensible is nonsense. This nonsense and the inherent contradictions predict the collapse of postmodern theory.

For example Duchamp always said that found objects, the readymades, were not art but a pastime chosen because they could never have anything to do with art, and yet exhibitions and museum collections continue to fill with found objects. So why did Duchamp deny the readymades, the found objects? Because readymades were not his idea, just as Fountain, the urinal, was not his idea. Both are by the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. John Higgs, in his book “Stranger than we can imagine” tells us that Elsa had been finding objects in the street and declaring them to be works of art years before Duchamp hit upon the idea of readymades'. The earliest that we can date with any certainty was Enduring Ornament, a rusted metal ring just over four inches across, which she found on her way to her wedding to Baron Leopold on 19 November 1913. On 11 April 1917 Duchamp wrote to his sister Suzanne and said that “One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”.

Duchamp made a major contribution to the epistemology of art when he made painting intellectual, then found himself unable to paint. He’d discovered the boundaries of visual art. There are limits to intellectual and visual language, conceptual limitations beyond which one can not make art. Duchamp’s error, (which he himself described as “breaking a leg, you didn’t mean to do it”) consisted of discarding the visual to make art intellectual. Here he followed ideas of his time also held by Walter Benjamin.

Walter Benjamin is a brilliant writer but he’s not who we think he is, he did not say what we think he said, or what we learned in school. He’s been praised as an early Marshall McLuhan, a social scientist able to discern the future of media. Yet on reading the text we find a political message that strays from the truth and then ignores it. Where we thought “The Work Of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” was research similar to today's academic scholarship, it is in fact Marxist propaganda. History reminds us that for Marxists truth and lies were a convenience; we can no longer read Benjamin innocently once we know he must follow the party line. Walter Benjamin said all we can ask of art is to reproduce reality. He writes that authorship, creativity, and aesthetics are outmoded fascist concepts, and the only valid art is that made by the working class for political use.

Some fifteen years ago I began to notice contradictions in postmodern theory that were bound to cause shifts in the cultural paradigm. One observation comes from the science of psychology which speaks of art therapy, of aesthetics as an organizing principle of mental health. Postmodernism is counter aesthetic, that’s bound to cause social discord and may even have nurtured the post-truth era.

In a 1959 interview transcribed on artspace.com, Duchamp was asked “Is there any way in which we can think of a readymade as a work of art?” To which he replied; That is a very difficult point, because art first has to be defined. Can we try to define art? We have tried. Everybody has tried. In every century there is a new definition of art, meaning that there is no one essential that is good for all centuries. So if we accept the idea of trying not to define art, which is a very legitimate conception, then the readymade comes in as a sort of irony, because it says, “Here is a thing that I call art, but I didn’t even make it myself.” As we know, "art," etymologically speaking, means “to hand make.” And there it is ready-made. So it was a form of denying the possibility of defining art, because you don’t define electricity. You see the results of electricity, but you don’t define it.”

Today we do define electricity; we also have more information on art, its history, it’s role in psychology, than was available to Duchamp, Benjamin, and Derrida, mainly coming from the science of art. Social anthropology posits that an aesthetic paradigm gave our primitive ancestors an advantage in propagating their genes. Paul Dirac, Steven Mithen, Dennis Duton, Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake, among numerous others, established a link between beauty and the highest evolutionary thinking of early hominids.

Science documents a number of non-verbal languages operating alongside the intellect; body language including dance, acoustic language including music, visual language, where a picture is worth a thousand words, the language of feelings, and the language of sensations among others. To reject aesthetics in favor of intellectual art meant discarding most of the vocabulary, syntax, and grammar of the non-verbal languages that inform intellect.

Denis Dutton says aesthetic taste is an evolutionary trait and is shaped by natural selection. It's not, as almost all contemporary art criticism and academic theory would have it, "socially constructed." Dutton argues, with forceful logic and hard evidence, that art criticism needs to be premised on an understanding of evolution, not on abstract theory.

“After Postmodernism” predicts a new movement emerging as a reaction to postmodern deviations, that once seen cannot be unseen. Meaning of course the errors swept under the rug, those contradictions swept under the discrete veil of art history. That Duchamp was wrong about so much yet praised for it, that Walter Benjamin was also wrong yet promoted, as so many artists, professors and writers since, this derived from the idea that art is anything that you can get away with.

That means essentially that the contemporary lacks standards, and the future of art can only proceed by defining art; by criteria. Every other profession knows what they are doing. Science has already done the job for us, it’s now a matter of publishing and disseminating that information until a critical number are informed, for change to happen, for a conversation to begin that asks what is art according to social function and personal experience. When art is anything then it is nothing; without limitations we dissolve in the boundless. Change begins once we recognize the need to know more than the cultural canon.

April 6, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

32-The Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Elsa Freytag-Loringhoven's "Fountain","God" and "Limbswish".

From the book by John Higgs, "Stranger than we can imagine".

In March 1917 the Philadelphia-based modernist painter George Biddle hired a forty-two-year-old German woman as a model. She visited him in his studio, and Biddle told her that he wished to see her naked. The model threw open her scarlet raincoat. Underneath, she was nude apart from a bra made from two tomato cans and green string, and a small birdcage housing a sorry-looking canary, which hung around her neck. Her only other items of clothing were a large number of curtain rings, recently stolen from Wanamaker's department store, which covered one arm, and a hat which was decorated with carrots, beets and other vegetables.

Poor George Biddle. There he was, thinking that he was the artist and that the woman in front of him, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, was his model. With one quick reveal the baroness announced that she was the artist, and he simply her audience. Then a well-known figure on the New York avant garde art scene, Baroness Elsa was a performance artist, poet and sculptor. She wore cakes as hats, spoons as earrings, black lipstick and postage stamps as makeup. She lived in abject poverty surrounded by her pet dogs and the mice and rats in her apartment, which she fed and encouraged. She was regularly arrested and incarcerated for offences such as petty theft or public nudity. At a time when societal restrictions on female appearance were only starting to soften, she would shave her head, or dye her hair vermilion. Her work was championed by Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound; she was an associate of artists including Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, and those who met her did not forget her quickly.

Yet the baroness remains invisible in most accounts of the early twentieth-century art world. You see glimpses of her in letters and journals from the time, which portray her as difficult, cold or outright insane, with frequent references to her body odour. Much of what we know about her early life is based on a draft of her memoirs she wrote in a psychiatric asylum in Berlin in 1925, two years before her death.

In the eyes of most of the people she met, the way she lived and the art she produced made no sense at all. She was, perhaps, too far ahead of her time. The baroness is now recognized as the first American Dada artist, but it might be equally true to say she was the first New York punk, sixty years too early. It took until the early twenty-first century for her feminist Dada to gain recognition. This reassessment of her work has raised an intriguing possibility: could Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven be responsible for what is often regarded as the most significant work of art in the twentieth century?

Baroness Elsa was born Else Hildegarde Plotz in 1874 in the Prussian town of Swinemunde, now Swinoujscie in Poland, on the Baltic Sea. When she was nineteen, following the death of her mother to cancer and a physical attack by her violent father, she left home and went to Berlin, where she found work as a model and chorus girl. A heady period of sexual experimentation followed, which left her hospitalized with syphilis, before she befriended the cross-dressing graphic artist Melchior Lechter and began moving in avant garde art circles.

The distinction between her life and her art, from this point on, became increasingly irrelevant. As her poetry testifies, she did not respect the safe boundaries between the sexual and the intellectual which existed in the European art world. Increasingly androgynous, Elsa embarked on a number of marriages and affairs, often with homosexual or impotent men. She helped one husband fake his own suicide, a saga which brought her first to Canada and then to the United States. A further marriage to Baron Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven gave her a title, although the Baron was penniless and worked as a busboy. Shortly after their marriage the First World War broke out, and he went back to Europe to fight. He took what money Elsa had with him, and committed suicide shortly afterwards.

Around this time the baroness met, and became somewhat obsessed with, the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp. One of her spontaneous pieces of performance art saw her taking an article about Duchamp's painting Nude Descending a Staircase and rubbing it over every inch of her body, connecting the famous image of a nude with her own naked self. She then recited a poem that climaxed with the declaration 'Marcel, Marcel, I love you like Hell, Marcel!'

Duchamp politely declined her sexual advances. He was not a tactile man, and did not like to be touched. But he did recognize the importance and originality of her art. As he once said, '[The Baroness] is not a futurist. She is the future.' (He turned out to be accurate.) Duchamp is known as the father of conceptual art. He abandoned painting on canvas in 1912 and started a painting on a large sheet of glass, but took ten years to finish it. What he was really looking for were ways to make art outside of traditional painting and sculpture. In 1915 he hit upon an idea he called 'readymades', in which everyday objects such as a bottle rack or a snow shovel could be presented as pieces of art. A bicycle wheel that he attached to a stool in 1913 was retrospectively classed as the first readymade.

These were a challenge to the art establishment: was the fact that an artist showcased something they had found sufficient grounds to regard that object as a work of art? Or, perhaps more accurately, was the idea that an artist challenged the art establishment by presenting a found object sufficiently interesting for that idea to be considered a work of art? In this scenario, the idea was the art and the object itself was really just a memento that galleries and collectors could show or invest in. Yet throughout his life, Duchamp insisted the readymades were not art, they were a pastime, chosen because they could not have anything to do with art.

Duchamp's most famous readymade was called Fountain. But is it true to say that Fountain was Duchamp's work? The answer as we find out later is a plain no. Fountain was a urinal which was turned on its side and submitted to a 1917 exhibition at the Society of Independent Artists, New York, under the name of a fictitious artist called Richard Mutt. The exhibition aimed to display every work of art that was submitted, so by sending them the urinal Duchamp was challenging them to agree that it was a work of art. This they declined to do. What happened to it is unclear, but it was not included in the show and it seems likely that it was thrown away in the trash. Duchamp resigned from the board in protest, and Fountains rejection overshadowed the rest of the exhibition. And yet R. Mutt had not paid the membership/entry fee that was the sole condition for being in the show, therefore the rejection was valid.

In the 1920s Duchamp stopped producing art and dedicated his life to the game of chess. But the reputation of Fountain slowly grew, and Duchamp was rediscovered by a new generation of artists in the 1950s and 1960s. Unfortunately very few of his original works survived, so he began producing reproductions of his most famous pieces. Seventeen copies of Fountain were made. They are highly sought after by galleries around the world, even though they need to be displayed in Perspex cases thanks to the number of art students who try to engage with the art' by urinating in it. In 2004, a poll of five hundred art experts voted Duchamp's Fountain the most influential modern artwork of the twentieth century.

On 11 April 1917 Duchamp wrote to his sister Suzanne and said that 'One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture; since there was nothing indecent about it, there was no reason to reject it.' As he was already submitting the urinal under an assumed name, there does not seem to be a reason why he would lie to his sister about a 'female friend'. The strongest candidate to be this friend was Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. She was in Philadelphia at the time, and contemporary newspaper reports claimed that 'Richard Mutt' was from Philadelphia.

If Fountain was Baroness Elsa's work, then the pseudonym it used proves to be a pun. America had just entered the First World War, and Elsa was angry about both the rise in anti-German sentiment and the paucity of the New York art world's response to the conflict. The urinal was signed 'R. Mutt 1917', and to a German eye 'R. Mutt' suggests Armut, meaning poverty or, in the context of the exhibition, intellectual poverty.

Baroness Elsa had been finding objects in the street and declaring them to be works of art since before Duchamp hit upon the idea of readymades'. The earliest that we can date with any certainty was Enduring Ornament, a rusted metal ring just over four inches across, which she found on her way to her wedding to Baron Leopold on 19 November 1913. She may not have named or intellectualized the concept in the way that Duchamp did in 1915, but she did practice it before he did.

Not only did Elsa declare that found objects were her sculptures, she frequently gave them religious, spiritual or archetypal names. A piece of wood called Cathedral (1918) is one example. Another is a cast-iron plumbers trap attached to a wooden box, which she called God. God was long assumed to be the work of an artist called Morton Livingston Schamberg, although it is now accepted that his role in the sculpture was limited to fixing the plumbers trap to its wooden base. The connection between religion and toilets is a recurring theme in Elsa's life. It dates back to her abusive father mocking her mother's faith by comparing daily prayer to regular bowel movements.

Critics often praise the androgynous nature of Fountain, for the act of turning the hard, male object on its side gave it a labial appearance. Duchamp did explore androgyny in the early 1920s, when he used the pseudonym Rrose Selavy and was photographed in drag by Man Ray. But androgyny is more pronounced in the baroness's art than it is in Duchamp's.

In 1923 or 1924, during a period when Baroness Elsa felt abandoned by her friends and colleagues, she painted a mournful picture called Forgotten Like This Parapluie Am I By You - Faithless Bernice! The picture included a leg and foot of someone walking out of the frame, representing all the people who had walked out of her life. It also depicts a urinal, overflowing and spoiling the books on the floor, which had Duchamp's pipe balanced on the lip.

comments: legrady@me.com

33-Close down the art schools... set those chickens free!

Ai WeiWei as drowned refugee and bird whose stomach is full of plastic,

Miklos Legrady, 33" x 48" - 83.82cm x 121.92cm, acrylic on cardboard, Feb. 04, 2017

Workers in Canada’s cultural sector earn 45% of an auto mechanic’s pay, but there’s a reason for that. If someone’s a recent art graduate, they're neither an artist nor a curator, but a high priest in an esoteric cult as far removed from art as homeopathy is from real medicine. The factory guy building a tractor is highly skilled, the university graduate mostly knows how to talk about the idea of art, but has not much by way of skills. Surprisingly there are few jobs looking for people who talk about art. This situation says the art world needs a serious shake up, a reformation, a revolution. I suggest shut down government art funds, the grant system, and close the art schools... set those chickens free!

Once the dust settles those who are still making art were real, the others were in it for the wrong reasons. A lot of people would lose their jobs, both artists and administrators supervising grant money. Music gets a pass, you can’t fake it with music. My orchestra piece, called 3’44”, has musicians playing seriously out of tune instruments; the audience would walk. Acoustic language, aural language can’t be faked, we have an instinct for music. Writing also needs skill or we stop reading when bored. Visual art needs a reboot. If we shut down the academy and government support, we’d lose the visual artists, the sculptors and installation artists, performance artists, we’d end up back in Shakespeare’s time, when people needed talent, technique, and mastery to practice their profession.

April 11, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

34-Why Duchamp?

Miklos Legrady, 25 " x 46" - 63.5cm x 116.84cm, acrylic on cardboard, January 2, 2016.

Duchamp was not talked about for some 40 years, from 1920 when he quit painting to 1960, when his ideas again meant something to American artists. In the 1920s it rapidly became evident that contradicting your taste and discarding aesthetics in favor of ideas didn’t lead anywhere, it degraded art for those interested in the complex shades of creativity.

By the 1960s the situation had changed. The G.I. bill allowing veterans a free university education created art schools across the country, whose graduating students would then find work in new art schools to accommodate a rising population. Academia looked like an anthill full of art students and came crashing against a contradiction.

Artists had always been recognized for their talent, genius, skills, experience, and deep vision. It was obvious that tens of thousands of these students lacked talent and the visionaries among them were few and far between, but they had all paid their tuition and academia owed them a degree. Brain storming finally led to a brilliant idea, the idea itself would be the aim of art. Students were taught to think of ideas, to speak of ideas, to live and breathe and eat ideas, t’was said the most important aspect of art.

Today we have scientific documentation on the origins and role of art in evolution and the production of culture. Back in the 1960s art was still “anything you could get away with”. So we wonder if postmodernism nurtured a post truth society and enabled Donald Trump, who always tries to see what he can get away with.

April 14, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

35-New York feels empty now

Miklos Legrady, 20" x 34" - 50.8cm x 86.36cm, acrylic on cardboard, November 21, 2015.

It's 1995. I’m with my brother in Soho; I live five minutes away on Stanton st., he's on Wooster st. in the thick of it. Broome street warehouses washed by winter sun, that cold yellow light on white painted brick. We visit one gallery after another. George says it feels like post-apocalyptic times. Money's gone, the market crashed, art world's dead and we're sifting through the ashes. We talked of Baldessari, his followers. Of the patronage system. Some of these galleries are museums, temples, fragments, histories, bread crumbs.

Aesthetics has a bad name in our time. Treated like a distant uncle who embarrassingly plagues our family gatherings, it's seen as a weakness, leftover from patriarchal times when wives dragged their husbands to the opera. At present the problem's misunderstood, the players confused. In fact at a discussion presented by the School of Visual Arts in New York, a panel of distinguished critics, learned art historians, and respected professors could not define the term. The lecture's theme (Crisis In Aesthetics) was referred to, drawn from, sketched lightly but never defined, as if unimportant. Aesthetics was unacceptable in 1995. One audience member suggested dispensing with aesthetics altogether, but that's like hanging first, trial after…

I’d studied at Rochester’s Visual Studies Workshop and apprenticed at Afterimage. There I met Charles Desmarais, a Cardinal Richelieu type upset by the chaos of sensual creation, one who finds order in concepts. Unfortunately Charles later occupied some influential posts. Enough to say that over three decades while on his watch, photography was deprecated, renamed as a lens-based practice that has very little to do with either beauty or fascination; photography transitioned into postmodernity and fell in status from art form to a simple document and tool.

Forward in time 22 years later, New York looks like a ship on waves of art history with crests and troughs. Still in conflict, New York has been an ongoing art disintegration that yet never loses mass because of it’s inner strength, continually refolding on itself, penetrating it’s own core then exploding to its perimeter to be drawn back like a solar flare. But California is not the solar core… though it’s warmer down there, and… Hollywood. In the 1950s postwar era, poor Europe, ravaged and beaten, was again battered and fell under the onslaught of CIA dollars promoting American art. Minerva, French art muse (that slut), followed the money landing in New York but moving to where the sun does shine, California. Which turned out to be surface and superficial.

Now SoCal is guilty of Conceptual art. Ideas belong to literature, to writing. Visual art is sensory, it’s about seeing, not reading. California breathed renewed life into flawed European theory. New York and California ring empty because postmodernism bears the seeds of its own demise in the nihilism of its mandate. Alarm bells ring at Marshall McLuhan’s famed 1960s observations, often misattributed to Warhol, that art is anything you can get away with. Such ethics say the arts pioneered a psychology of denial whose mature form finds expression in Trump’s post-truth politics. Did postmodernism foster a cult of denial that now has taken presidential form? The canary in the mine is coughing.

The Book of Changes is one of the Five Classics of Confucianism. Of self-destruction it writes that nihilism is not destructive to the good alone but also destroys itself; that which lives solely by negation cannot continue on its own strength alone. We now reclaim the art dialectic, the etymological, to create a new art movement on postmodern ashes.

April 14, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

36-Lies my teacher told me.

Miklos Legrady, 33" x 49" - 83.82cm x cm x 124.46cm, acrylic on cardboard. Sept. 24, 2015.

In a recent online survey, hundreds of the world’s top art experts agreed that Duchamp’s Fountain, or urinal, is the most important work of art of the 20th century. It is unsettling to recognize that hundreds of the world’s top art experts are completely wrong. What’s even worse is that for decades no one noticed although the facts were on the table.

First, the Fountain is not by Duchamp, there’s solid proof that the urinal is by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, a friend of Duchamp’s who 4 years before him was exhibiting found objects as art. We need to update our art history to show that found objects are Elsa’s idea and not Duchamp’s. Second, Duchamp consistently said found objects are not art. A third wrong becomes obvious when deconstructing the urinal; if scatology is our most important art this culture is in serious trouble. Those who think that art is to piss on should now leave the field to those with higher standards.

What’s even worse than hundreds of experts being wrong for forty years was that no one noticed. What does this say about our art theory and those artists whose ideas were seminal to postmodernism? We learn that Duchamp made painting intellectual but then stopped painting. Jasper Johns wrote that Duchamp tolerated, even encouraged the mythology around that ‘stopping’, “But it was not like that … He spoke of breaking a leg. ‘You didn’t mean to do it’ he said”. Duchamp had located the boundaries of visual art, discovered that intellectual painting was dysfunctional; visual art needs those non-verbal aesthetics called visual language.

Walter Benjamin also fails peer review because his writing follows Marxists theory and toes the party line: Marxists see truth and lies as equally useful strategies in a class war. That explains why Benjamin’s “Mechanical Reproduction” is so distorted on the procrustean bed of working class mythology. Such policy did not age well yet Benjamin is still revered by an academic generation whose adulation lacks both scholarship and common sense.

The fruit does not fall far from the tree. Sol Lewitt’sSentences on conceptual art and Paragraphs on conceptual art show a severe failure of logic; his writing makes no sense. Lewitt counters these charges by saying a conceptual artist is a mystic who overleaps logic, but he fails to explain how such miracles happen. It’s an ill omen no one noticed the obvious or thought this through… respect for authority is the enemy of inquiry.

MOMA curator (and now Dean of Fine Arts at Yale) Robert Storr observed that in the 1960s the art world moved from the Cedar Tavern to the seminar room. But in the seminar room, fine art practice unavoidably follows art theory, which puts Descartes before the horse, and so our postmodern academic practice takes us as far from real art as homeopathy is from real medicine. If we have not seen as far as others, it's because we’re standing on the shoulders of very short giants, or else short-sighted giants are standing on our shoulders.

April 16, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

37-Curatorial and editorial control

Miklos Legrady, 24" x 34" - 60.96cm x 86.36cm, acrylic on cardboard, May 11, 2016

Should we mourn the death of the artist, and celebrate the rise of the creative curator? Do they set the agenda? I posed this question years ago and was asked if I realized how hard a curator’s job was? Really? As artist and writer we must write and paint what we want. Then it’s on us to create something that is worth reading, worth looking at.

April 25, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

38-Deconstructing Walter Benjamin

Miklos Legrady 26" x 36" - 66.04cm x 91.44cm, acrylic on cardboard. October 18, 2015

I started work on a book this week, it starts with this critique of Walter Benjamin.

[3333 words]

I’m going to hurt your feelings and it’s going to upset you, but Walter Benjamin did not say what you think he said, nor what they said about him, nor what we learned in school. It is hard to believe we were delusional for decades, but then medieval monks counted angels dancing on the head of a pin and we’re not that far ahead; our political beliefs look plausible at the moment but seriously need corrections.

Sometimes valid reasons exist to criticize, question, and disagree if we must. It’s time to ask if Benjamin spoke truth, did his theories and predictions stand the test of time? This paper does not condemn Walter Benjamin who was a highly talented writer, but it does condemn the failure of his social science in The Work Of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

As an aside, Joseph Henry tells us Benjamin’s essay should be titled “Technological Reproductability” instead of “Mechanical reproduction”, following the canonical translation of Benjamin scholars like Michael Jennings.”(0) There’s objections to this academic pretence. Jenning’s translation is awkward, unpronounceable, and semantically inaccurate for that era. It was submission to authority that doomed Benjamin’s vision, turned what should be social science into science fiction.

Benjamin presents a historical stream of art that was ritualized by priests at the dawn of time to control a gullible populace. But in the nineteenth century “the age of mechanical reproduction separated art from its basis in cult, the semblance of its autonomy disappeared forever… the very invention of photography had… transformed the entire nature of art”.

Walter Benjamin has been praised as an early Marshall McLuhan, a social scientist able to discern the cultural effects of media. As an intellectual communist Benjamin was versed in the classical Marxist tradition, Marx, Engels, their contemporaries, and then Kautsky, Plekhanov, Lenin, Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg. Where we thought The Work Of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction was research similar to today's academic scholarship, it is in fact Marxist propaganda. On reading the text we find a political message that strays from the truth and then ignores it. History reminds us that communists saw truth and accuracy as useful when convenient; we cannot read Benjamin innocently when the work has political priorities. Benjamin says that all we can ask of art is to reproduce reality, that creativity is an outmoded concept, but he’s writing agitprop without concern for accuracy. As we shall see, he shares flawed assumptions, fact and fiction twisted to fit theory; the reductions, contradictions, and leaps of faith are obvious.

One of his last works, Theses on the Philosophy of History, seemingly doubts Karl Marx's claims to scientific objectivity; this time Benjamin appears to rejects the past as a continuum of progress and suggests historical materialism is a quasi-religious fraud. But that comes later; Mechanical Reproduction is based on dialectic materialism, denying creativity and aesthetics in favor of a data-driven art whose purpose is degraded to propaganda. Since then science has shown that beauty and its complex differentiations are crucial for mental health. In the 1970s Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake analyzed links between beauty, information processing, and information theory. Physicist Paul Dirac said that if one works at getting beauty in one's equations, and if one has a really sound insight, one is on a sure line of progress. Lacking beauty would hinder progress.

Benjamin was no beauty, he was an awkward man. Hannah Arendt writes of him “With a precision suggesting a sleepwalker his clumsiness invariably guided him to the very centre of a misfortune”. For example to escape the bombing of Paris he so feared, he had moved to the outlying districts of the city and unwittingly ended up in a small village that was one of the first to be destroyed. Benjamin had not realised this apparently insignificant place was at the centre of an important rail network, and therefore liable to be targeted. (1) In Mechanical Reproduction we see Benjamin stumbling just as much from one mistaken idea to the next in his role as social scientist, but here his misfortune comes from his ideology. He has to explain the mechanical art paradigm as though Marx’s prognosis was accurate, which it was not, so like dominoes the entire thesis and conclusions fall flat. The essay starts with incorrect Marxist beliefs, builds layers of expectation on those mistakes thus compounding the inaccuracy, until eventually we see the entire history and prognostic structure is a fantasy, a tall tale.

“The criterion we use to test the genuineness of apparent statements is the criterion of verifiability”, Oxford’s A.J. Ayers writes in a study of language, truth, and logic. “We say that a sentence is factually significant to any given person if, and only if, they know how to verify the proposition it purports to express”(2) Georgy Pyatakov, who was twice expelled from the Party and eventually shot, wrote that a true Bolshevik is “ready to believe [not just assert] that black was white and white was black, if the Party required it.” In Orwell’s book 1984, O’Brien proclaims this very doctrine - two plus two is really five if the Party says it is - which he calls “collective solipsism.” (3)

In Mechanical Reproduction we find beliefs that seem incredible without a Marxist indoctrination. One Communist writer who later left the party in disillusionment was Arthur Koestler. In The God That Failed and The Invisible Writing he described the logical contradictions and resulting sacrificium intellectus that Communist writers suffered. The resulting emotional damage may well explain Benjamin's catastrophic failure of morale, which can happen to Marxists when they are left alone for too long, perhaps leading to his subsequent suicide in a moment of crisis when “with a precision suggesting a sleepwalker his clumsiness invariably guided him to the very centre of a misfortune”.

Arthur Koestler wrote of Benjamin's death in France during the 1940s in The Invisible Writing. “Just before we left, I ran into an old friend, the German writer Walter Benjamin. He was making preparations for his own escape to England. He has thirty tablets of a morphia-compound, which he intended to swallow if caught: he said they were enough to kill a horse, and gave me half the tablets, just in case. The day after the final refusal of my visa, I learned that Walter Benjamin, having managed to cross the Pyrenees, had been arrested on the Spanish side, and threatened with being sent back to France the next morning. The next morning the Spanish gendarmes had changed their mind, but by that time Benjamin had swallowed his remaining half of the pills and was dead.” (4)

Benjamin’s literary talent shows best in Passagenwerk or Arcades Project, an unfinished work written between 1927 and 1940. An enormous collection of writings on the city life of Paris in the 19th century, many scholars consider Arcades might have become one of the great texts of 20th-century cultural criticism, but was never completed due to his suicide. This extract is from his notes on Marseilles;

“the yellow-studded maw of a seal with salt water running out between the teeth. When this gullet opens to catch the black and brown proletarian bodies thrown to it by ship’s companies according to their timetables, it exhales a stink of oil, urine, and printer’s ink. This comes from the tartar baking hard on the massive jaws : newspaper kiosks, lavatories, and oyster stalls. The harbour people are a bacillus culture, the porters and whores products of decomposition with a resemblance to human beings. But the palate itself is pink, which is the colour of shame here, of poverty. Hunchbacks wear it, and beggarwomen. And the discoloured women of rue Bouterie are given their only tint by the sole pieces of clothing they wear: pink shifts.”(5) |

Benjamin’s literary talent and virtuosity reveal a genius, one that in Mechanical Reproduction was reshaped on the procrustean bed of Marxist doctrine.

He imagined the role of art in prehistoric times as a religious opiate, rituals invented by the ruling class to control workers, whereas in fact religion, politics, and life were undifferentiated in those early days, one lived in a world of magic in which the gods were everywhere; a crash of lighting accompanied by horrendous thunder was quite persuasive of the god’s presence and mood. Works of art like images, costumes, body paint, and sacred objects all served in religious rituals but were also found in everyday life; there was an aesthetic process to the making of daily objects that gave them a beauty quite unnecessary to their utilitarian practice.

In clothing, beads, body decorations and tool making began the practice of art whose etymology can be understood when we speak of the art of cuisine or the art of conversation. There is a human instinct to create beautiful things, to give expression to an aesthetic algorithm born in the depths of the unconscious mind. Denis Dutton was a philosophy professor and editor of Arts & Letters Daily. In The Art Instinct he suggested that humans are hard-wired to seek beauty. “There is evidence that perceptions of beauty are evolutionarily determined, that things, aspects of people and landscapes that are considered beautiful are typically found in situations likely to give enhanced survival of the perceiving human's genes.” Dutton argues, with forceful logic and hard evidence, that art criticism needs to be premised on an understanding of evolution, not political theory.

Art gave a personal style to utilitarian objects, and that took time and effort so beautifully made objects were recognized as valuable. We must also consider music as awakening an aesthetic paradigm. We read in old England songs were everywhere; the maid milking or the farmer driving his cows to pasture had their song, the soldiers had their own. The deep effect of music on the soul must be taken into account when we imagine primitive hunter-gathering life. It is likely they had a complex sense of beauty and a finesse of feelings and moods that both music and art awaken, so we question Benjamin’s oppressor-oppressed binary as the sole agent of civilization. There were other human drives and motivations beside class struggle; of course conflicts were constant but they’re not the only template by which history can be read.

The Work Of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction opens with a 1931 quote by Paul Valéry on industrial technology transforming culture so much that it may bring about an amazing change in our very notion of art. As we read Benjamin’s paper a materialistic philosophy rejecting spiritual and individual values must be kept in mind. An opposite reading from psychology and archaeology sees art instead as an activity driven by instinct relatively unaffected by any specific technology; the art of our stone age ancestors does not much differ in intent from that of performance artist Marina Abramovi?. Technology may change but the primary drive remains an ancient algorithm, an instinct of human behavior born in the dawn of time millions of years ago.

Benjamin’s preface contains the seeds of it’s own demise as he writes of Marx’s critique having prognostic value, describing how capitalism would exploit the proletariat with increasing intensity, but ultimately create conditions which would make it possible to abolish capitalism itself. What actually happened was the opposite. The worker’s unions created the middle class, and massive union retirement funds were invested in capitalism, allowing anyone to become an invested owner of the means of production. Benjamin’s prognostic misconceptions tumble over each other like dominoes.

| the art of the proletariat after its assumption of power… or the art of a classless society… brush aside a number of outmoded concepts, such as creativity and genius, eternal value and mystery. |

Today’s documentation of genius attests to child prodigies and exceptional adults, while the spiritual aspect of values and mystery give a meaning to life, a psychological function that cannot be underrated. When psychology speaks of art therapy the opposite is also true; rejecting aesthetics and spiritual values degrades mental health, lowers morale and motivation, weakens character, and likely played a role in Benjamin’s suicide.

Inchapter 1 Benjamin writes that for the first time in the process of pictorial reproduction, photography freed the hand of the most important artistic functions. This artistic function is explained as representing reality; Social Realism. (chapter XI). Today we learn otherwise from Albert Mehrabian, born in 1939 to an Armenian family in Iran and currently Professor Emeritus of Psychology, UCLA. He is known for his publications on the relative importance of verbal and nonverbal messaging. His findings on inconsistent messages of feelings and attitudes have become known as the 7%-38%-55% rule (6) on the relative impact of words, tone of voice, and body language in speech. Ditto the relative importance of the hand in visual language, the unconscious statements and subliminal codes embedded in brush strokes are what make Van Gogh’s work so popular.

Chapter 2 holds the core of Walter Benjamin’s argument; “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art”. He’s wrong - books are made by mechanical reproduction yet stories and authors retain their magic as much as any work of art. Munch's The Scream is known from reproduction yet remains haunting, as haunting as any Raven perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door. Benjamin's reaching for hard facts, but art is about the magic.

Chapter 3 offers a confusing definition of aura as “the unique phenomenon of distance”. The masses will no longer let works of art be kept from them, instead ownership by the working class will lead to a familiarity that destroys the art’s aura, leaving no mystery to art. In effect, familiarity breeds contempt, so reproduction will devalue images. This was also wrong since the opposite happened. Instagram’s billion dollar evaluation reflectsthe public’s interest in their images. Benjamin talks of “the adjustment of reality to the masses and of the masses to reality”, with a nod to communist practice of thought control. Once the supposed religious mystery is dispelled from a work of art, art turns political, becomes propaganda adjusting the masses to communist reality.

In chapter 4 the aura is also described as uniqueness; “the unique value of the ‘authentic’ work of art” and so mechanical reproduction destroying the uniqueness destroys the aura. Photography is given as an example “The status of a work of art will no longer depend on a parasitic ritual (of authorship).From a photographic negative, for example, one can make any number of prints; to ask for the ‘authentic’ print makes no sense”.

History has not been kind to Benjamin; 150 years later, an authentic print by Ansel Adams sold for $722,000 because of the limited edition, the uniqueness of the work. Original photographs by Ansel Adams are defined as photographs printed by Ansel Adams from the negatives he made (photographed and developed). Art was always the personal touch. Mechanical aspects standardize photography but there’s plenty of scope for the artist's individual choices in the visual grammar of tone, shade and composition, and these determine the work. Although Benjamin often mentions printing and lithography even from medieval times, he totally ignores the popularity of the limited edition print and discounts the aesthetic factors that made the work desirable, since these are of no concern within his political orientation. Yet it is that very blind spot which forestalls his misfortune.

Through chapters 5 onward, Benjamin writes about film, which to him represent the final form of art that overrides all other images by being the most realistic.

“The age of mechanical reproduction separated art from its basis in cult, the semblance of its autonomy disappeared forever… the very invention of photography had… transformed the entire nature of art”. “for contemporary man the representation of reality by the film is incomparably more significant than that of the painter since it offers… a reality which is free of all [personal bias]. And that is what one is entitled to ask from a work of art. |

That’s a description of Social Realism; today we expect more from art than the obvious. We also know that personal bias is vital to what makes a work of art.

Further on the influence of painting is compared to film. Benjamin claims that film is politically progressive compared to the reactionary choice of looking at a painting: “Mechanical reproduction of art changes the reaction of the masses toward art. The reactionary attitude toward a Picasso painting changes into the progressive reaction toward a Chaplin movie.” Viewing a painting is a personal affair; with a painting “there was no way for the masses to organize and control themselves in their reception”. For communists the masse’s reaction is important; it is a reaction to be controlled by the politics telling us how we are to understand the meaning of a work. A film better lends itself to indoctrination because it is seen by large groups at the same time. Benjamin mentions Duhamel’s reaction; “I can no longer think what I want to think. My thoughts have been replaced by moving images.”(7)

The Epilogue degrades into word salad.

The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life. The violation of the masses, whom Fascism, with its Führer cult, forces to their knees, has its counterpart in the violation of an apparatus which is pressed into the production of ritual values. |

As proof Benjamin quotes the fascist artist Marinetti’s manifesto on the Ethiopian colonial war.

War is beautiful because it establishes man’s dominion over the subjugated machinery by means of gas masks, terrifying megaphones, flame throwers, and small tanks. War is beautiful because it enriches a flowering meadow with the fiery orchids of machine guns…” |

Benjamin concludes his essay by writing “This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.” “The work of art becomes a creation with entirely new functions, among which the one we are conscious of, the artistic function, later may be recognized as incidental.” If the artistic function is incidental then the work is no longer art, it’s political illustration. By the end of his paper Benjamin’s argument had degenerated because of the contradictions at its core.

Any conclusions would acknowledge the beauty of Benjamin’s writing and the discipline of his political thinking, which lend a hypnotic gravitas to his essay. Til recently his political affiliation would have enhanced his credibility among the greatest thinkers of the times; John Berger’s essay on art criticism Ways of Seeing owes a debt to Benjamin. Which also means that Berger’s views in Ways of Seeing are flawed and invalid wherever they are based on Benjamin’s writing. Marxism finally lost its aura, its authority, after the dissolution of the Soviet empire in 1991.

0- Joseph Henry, “All Awareness Becomes Base”: Jens Hoffmann’s Reduction of The Arcades Project, MOMUS http://momus.ca/awareness-becomes-base-jens-hoffmanns-reduction-arcades-project/

1-Giorgio van Straten, ‘In Search of Lost Books’, translated from the Italian by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell, Pushkin Press.

2- A.J.Ayers, Language, Truth and Logic, p48, Pelican Books.

3- Gary Saul Morson, The house is on fire! On the hidden horrors of Soviet life. The new Criterion. https://www.newcriterion.com/articles.cfm/The-house-is-on-fire--8466

4- Arthur Koestler, p. 421, The Invisible Writing, Hamish, Hamilton & Collins

5- Walter Benjamin, Neue schweizer Rundschau, April 1929. Gesammelte Schriften, IV, 359-364. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. It has been collected in English translation in his Selected Writings II (Belknap Press 1999).

6- Albert Mehrabian https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Mehrabian

7- Georges Duhamel, *Scènes de la vie future*, Paris, Mercure de France, 1930, p. 52.

February 27, 2019

comments: legrady@me.com

May, 2019 -->