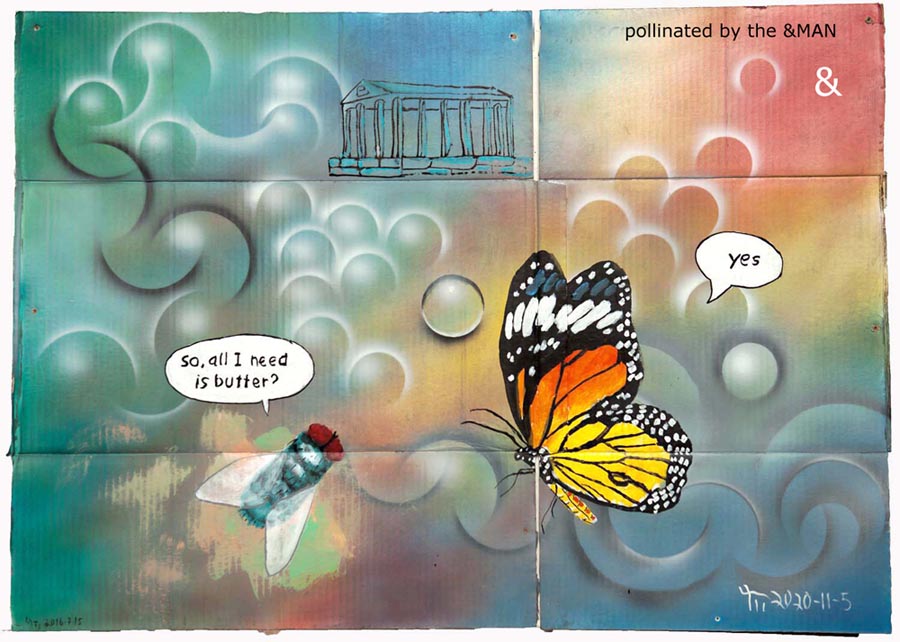

Miklos Legrady, 29" x 40" - 71.12cm x 101.06cm, acrylic on cardboard, Nov.5, 2020

Miklos Legrady, 29" x 40" - 71.12cm x 101.06cm, acrylic on cardboard, Nov.5, 2020The Artwork of The Naked Ape

Michel Foucault says that “in every society the production of discourse is at once controlled, selected, organized and distributed”(1), and American sociologist Herbert J. Gans writes of the “gatekeepers” of the art world. (2) Repeated complaints from peers on Facebook tell us that over the last three decades, academics have censored the art shown, restricting it to intellectual values, and in doing so they may have throttled the muse, poor thing. Most fine arts producers graduate from similar schools and share the same values, which are reflected in their association, their production, and the systems created thereby… surely a cultural blindness results from such group judgments.

This homogeneity includes limiting participation to those sharing the same outlook and language, narrowing the game to believers in a common ideology, in effect creating a tautology… the urge to belong defines what is permissible. Danielle S. McLaughlin of the Canadian Civil Liberties Associationk said when we can no longer explore and express ideas that are troubling and even transgressive, we are limited to approved doses of information in community-sanctioned packets.

Derrida’s method of deconstruction was to look past the irony and ambiguity to the layer that genuinely threatens to collapse that system. He would have loved the notion that to be successful today an artist must look the part and talk the talk. It follows that where there’s a territory there must be a script, a model, a style; an orthodoxy that subverts, negates and contradicts originality.

What of the present? Blake Gopnik tells us that “We cherish everything in American art that is difficult, conceptual, anti-aesthetic, tough, and unsparing. Those were the neo-Dada values that began to win out in the early 1960s”. (3) At a panel discussion on diminishing public interest in contemporary art, Robert Storr, then MOMA curator, said “in the 1960s the art world moved from the Cedar Tavern to the seminar room.” (4) We infer that academics gamed the system and tenure track has stifled the arts, till the poor thing is nearly dead. Will art perish? Can we finally dispense with the art object and be just… you know… smart?

Richard Shiff reminds us “Clement Greenberg… warned of applying conceptual order to aesthetic judgment… when critics argue that any emotional or intellectual position must always derive from an existing cultural construct, they… dismiss the feeling of their own experiences….” (5)

So how do we check our attitude and speak a different language? We first scratch at the psychology of art. Carl Jung writes of four mental functions; sensation, feelings, intellect, and intuition. There are three modes of comprehension other than the intellectual one. Jung writes that shallow individuals rely on a primary function but the inclusion of other modalities gives that individual depth. We who rely on the intellect forget that it can only operate within the known and is limited by the extent of our knowledge, yet it’s greatest flaw is always to assume that what we know, is all that is important.

I am under the impression that we not only can, but also need to answer the challenges of current Canadian art, overcoming out patterns and vested interests; we can see beyond our blind spot if we step outside what we’ve been led to believe and review the evidence with fresh eyes.

And yet I am reminded that Michel Foucault, in his lectures at the College de France in 1983-84, titled “The Courage of Truth” (6) warned us of the danger of parrhesia, of speaking openly and honestly against established and vested interests, reminding of Socrates’ fate.

On the same cautionary note, statistician R.A. Fischer in1947 was invited to give a series of talks on BBC radio about the nature of science and scientific investigation. His words are so relevant to the arts today. “A scientific career is peculiar in some ways. Its reason d’être is the increase in natural knowledge and on occasion an increase in natural knowledge does occur. But this is tactless and feelings are hurt. For in some small degree it is inevitable that views previously expounded are shown to be either obsolete or false. Most people, I think, can recognize this and take it in good part if what they have been teaching for ten years or so needs a little revision but some will undoubtedly take it hard, as a blow to their amour propre, or even an invasion of the territory they have come to think of as exclusively their own, and they must react with the same ferocity as (animals whose territory is invaded). I do not think anything can be done about it… but a young scientist may be warned and even advised that when one has a jewel to offer for the enrichment of mankind some will certainly wish to turn and rend that person.” (7)

Margaret Heffernan on the other hand, in “Dare to disagree”, insists on the importance of speaking out. “The fact is that most of the biggest catastrophes that we've witnessed rarely come from information that is secret or hidden. It comes from information that is freely available and out there, but that we are willfully blind to, because we can't handle, don't want to handle, the conflict that it provokes. But when we dare to break that silence, or when we dare to see, and we create conflict, we enable ourselves and the people around us to do our very best thinking.” (8)

And so with Margaret Heffernan in mind we look at three artists to change the way we think about art. These artists are compromised yet much of our thinking is based on them, their words are pillars of postmodernism. By questioning our premises we can only improve our understanding.

Walter Benjamin’s "The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction" (9) as seen as pure research akin to today's academic scholarship when it is actually a calculated political marketing tool denouncing individual creativity and promoting the dictatorship of the working class. Walter Benjamin was responsible to the Soviet Writer’s Committee and his work toes the party line; we cannot read Benjamin innocently knowing the political priorities. “Mechanical Reproduction” has no concern for accuracy or facts... woven with flawed assumptions, fact and fiction twisted to fit political theory, the reductions, contradictions, and leaps of faith are obvious; a reality check bounced.

Benjamin writes that talent is meaningless, the individual worthless, the only worthwhile art is made by the collective; authenticity is archaic. “From a photographic negative, for example, one can make any number of prints; to ask for the ‘authentic’ print makes no sense.” Today, 80 years later an authentic Ansel Adams or Edward Weston printed by the artist sells for over $80,000 and the reality and worth of authorship have been validated beyond question. Benjamin writes “The art of the proletariat… brush aside a number of outmoded concepts, such as creativity and genius”. He also tells us that aesthetics are a fascist illusion and the only worthwhile art is political propaganda.

Where we thought “The Work Of Art In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction” was research similar to today's academic scholarship, it is in fact Marxist propaganda. At the core of Benjamin’s argument is that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art. He’s wrong in that books are made by mechanical reproduction yet stories and authors retain their aura as much as any work of art. Munch's The Scream is known from reproduction yet remains haunting, as haunting as any Raven perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door. Walter Benjamin has been praised as an early Marshal McLuhan, a social scientist able to discern the cultural effects of media. Yet on reading the text we find a political message that strays from the truth and then ignores it.

Walter Benjamin was mistaken. Though he writes in a beautiful language, he failed the reality test; we need to acknowledge this and update our history books, to question what we take for granted, in this case our devaluation of aesthetics.

“Ideas alone can be works of art," Sol Lewitt proposed in his epic "Sentences on Conceptual Art," a primer on the ins and outs of postmodern art making. Ideas "need not be made physical," he continued. "A work of art may be understood as a conductor from the artist’s mind to the viewer’s. There's the possibility that the idea may never reach the viewer, or that the idea may never leave the artist’s mind. But all ideas are art if they are concerned with art and fall within the conventions of art." (10) The contradiction is obvious; if art is a conductor then any idea that remains in one’s mind and never reaches the viewer cannot by definition be art. From experience and history we know that art is content, not conductor; the medium is the conductor. Lewitt escapes criticism by claiming to be a mystic who overleaps logic, but nothing evades logic, not even the illogical. Do we believe that conceptual artists are mystics who overleap logic? In spite of this Sol Lewiit has been recast as the logician par excellence. Sol Lewitt said that an idea was art but he was wrong... an idea is science. Art is in the making, the reality check. If an idea were art, quality is moot as the work (as in work) cannot judged; they dissolve in the boundless.

“Vision and Visuality” sponsored by the Dia Art Foundation, Rosalind Kraus mentioned that Duchamp despised optical, ocular art (except for Manet) and disliked artisanal work, hence the ready-made. Yet ocular, optical art takes years to achieve and artisanal work is done with loving patience, these are things to respect, not to despise. We would be surprised to read that Shakespeare despised grammar, or that Stravinsky loathed musical notes. In a 1986 BBC interview with Joan Bakewell, Duchamp claimed the conceptual mantle when he said that until his time painting was retinal, what you could see, that he would make it intellectual. Today we know that Duchamp made no more paintings after he made painting intellectual. Marcel Duchamp needed to differentiate himself, to create his own brand as a Dadaist. He did this by rejecting the Impressionists. In Cabane's interview we read Duchamp wanted to destroy art. He actually destroyed his own ability to make art. “It was like a broken leg” he said and retired to play chess. If you tell yourself art is not worth the making and say it long enough, eventually you believe yourself and lose interest in making art. Instead of being a cautionary tale, Duchamp is recommended practice today and the results are toxic.

We should no longer think of art as arbitrary but as biology. Denis Dutton described the role of art in a Darwinian theory of evolution in his book and in his Ted talk “The Art Instinct” (11), where he suggested that humans are hard-wired to seek beauty. “There is evidence that perceptions of beauty are evolutionarily determined… likely to enhance survival of the perceiving human's genes.” Physicist Paul Dirac said that beauty in one’s equations, if the concept is valid, means a certainty of success. Neuroscientists in Great Britain discovered that the same part of the brain that is activated by art and music was activated in the brains of mathematicians when they looked at math they regarded as beautiful. (12) Then in the 1970s Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake analyzed links between beauty, information processing, and information theory. We now know that beauty and its complex differentiations are crucial for mental health, while science and psychology show that aesthetics are vital to the evolution of consciousness.

We need to reconsider the values we have inherited from Duchamp. How many have a urinal in their living room? Cleverness and toilet humor get tiresome after a while and those who truly believe art is to piss in should leave the field to those with higher spiritual values. Dada has lived its time, has withered and faded, now past the shelf date. These cultural shifts rewriting our mission statement may in fact be the most likely change occurring in the near future; we can help shape that.

In the world of nature we find that a bee’s dance informs the hive of the location of a field of flowers with sun-oriented hourly-based data, including the caloric value of that patch. Such unconscious yet precise content in the dance of a bee leads to far reaching speculation on unconscious content in the artwork of the naked ape.

(1) Michel Foucault, The Discourse on Language, Dec. 2, 1970

https://brocku.ca/english/courses/4F70/discourse.php)

(2) Herbert J. Gans, Public Ethnography, http://herbertgans.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Public-Ethnography.pdf)

(3) http://blakegopnik.com), July 25, 2016

(4) "Invisible Ink: Art Criticism and a Vanishing Public," sponsored by Art Table and the American chapter of the International Association of Art Critics at the American Craft Museum on May 15, 1996. http://studiocleo.com/cauldron/volume3/confluence/miklos_legrady/text/storr.html)

(5) Richard Shiff, Cliché and a lack of feeling, The Art Newspaper, 5 June 2015 http://theartnewspaper.com/comment/reviews/exhibitions/156620/)

(6) Michel Foucault, p10, p36, The Courage of Truth, Lectures at the College de France 1983-1984, Palgrave Macmillan, St. Martin’s Press 2008.

(7) David Salsburg, p51, The Lady Tasting Tea – How Statistics Revolutionized Science. Holt, N.Y. 2001

(9) Walter Benjamin, The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction,

https://legrady.com/benjamin.html)

(10) Sol Lewitt, Sentences on Conceptual Art, http://altx.com/vizarts/conceptual.html)

(11) Dennis Dutton The Art Instinct https://youtube.com/watch?v=PktUzdnBqWI)

(12) Mathematical beauty activates same brain region as great art, 13 February 2014 https://ucl.ac.uk/news/news-articles/0214/13022014-Mathematical-beauty-activates-same-brain-region-as-great-art-Zeki)