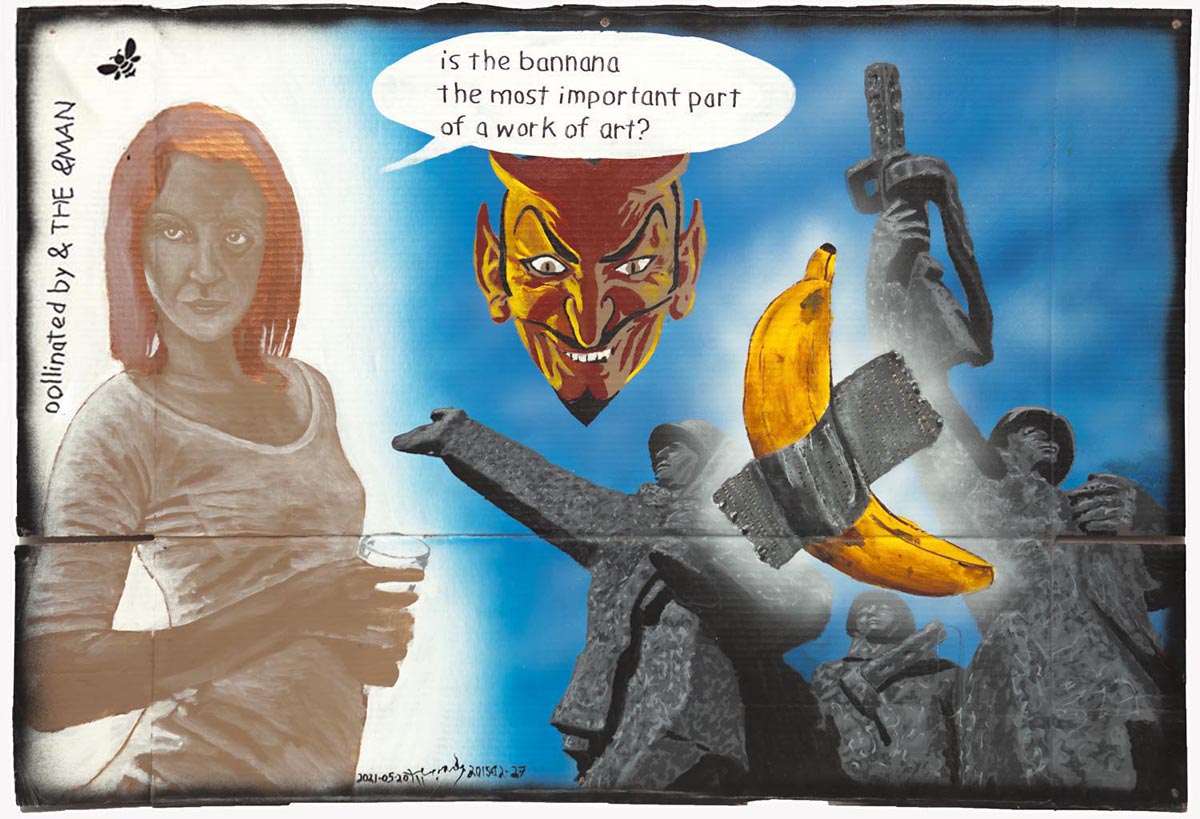

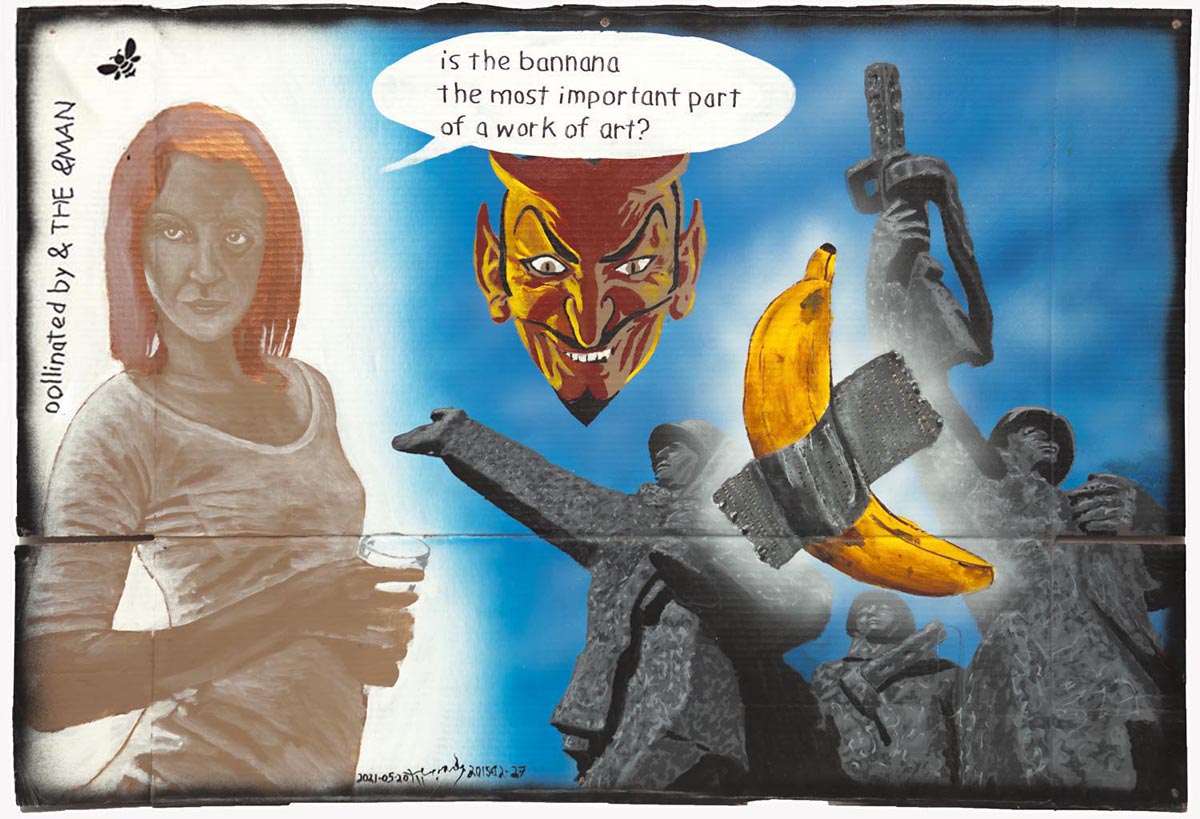

paintings by Miklos Legrady

Let’s Clean up Art History

We have the receipts

This article lifts a corner of the rug under which we sweep inconvenient facts. We’re not in Kansas anymore, this isn’t vanilla. "There is a really common tendency in academia for someone to come up with an idea, and that idea checks enough boxes that it's a convenient enough solution and no one really questions it. The reason it's important to have a really healthy dose of skepticism then, is when you really do question established consensus, you might just discover serious problems that haven't been unearthed yet, because no one has looked at it from that angle before." Graham Scheper. 0

We have been teaching our students an art history often contradicted by actual events, and an art theory based on self-serving assumptions, many of which made no sense. In an age of mechanical reproduction like paper print, this was hard to prove; it might take months or years of snail mail before we had access to the receipts, the documented evidence. Internet research now allows am immediate perspective.

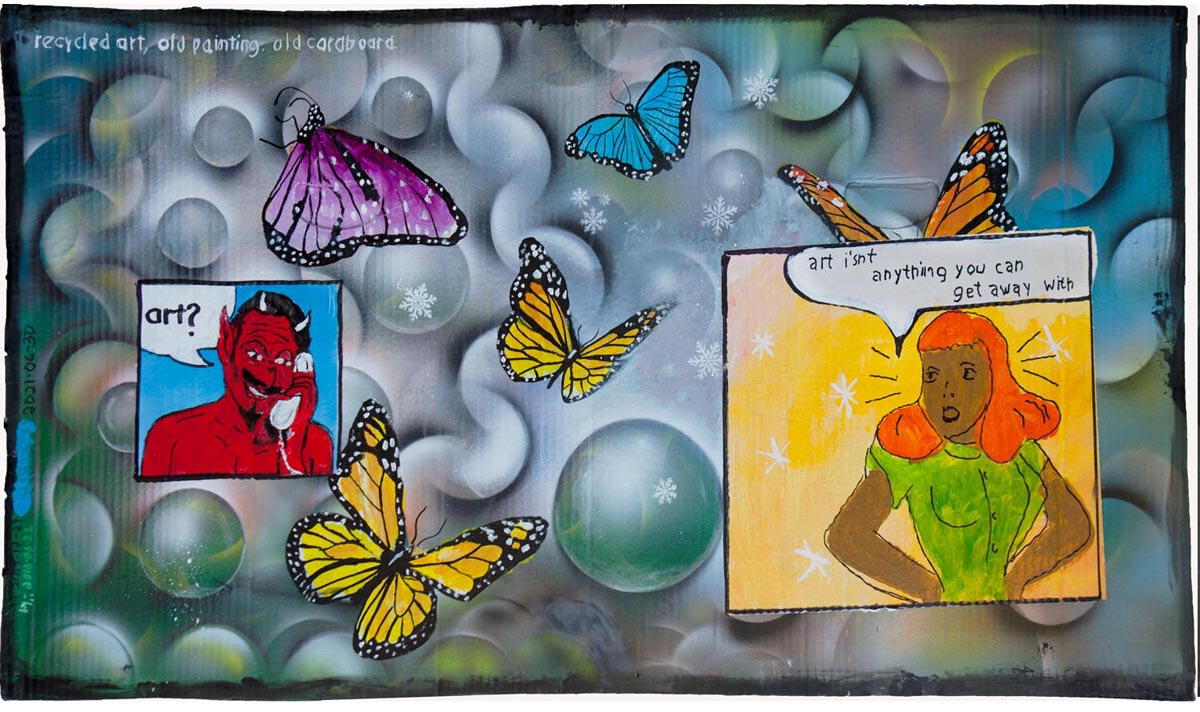

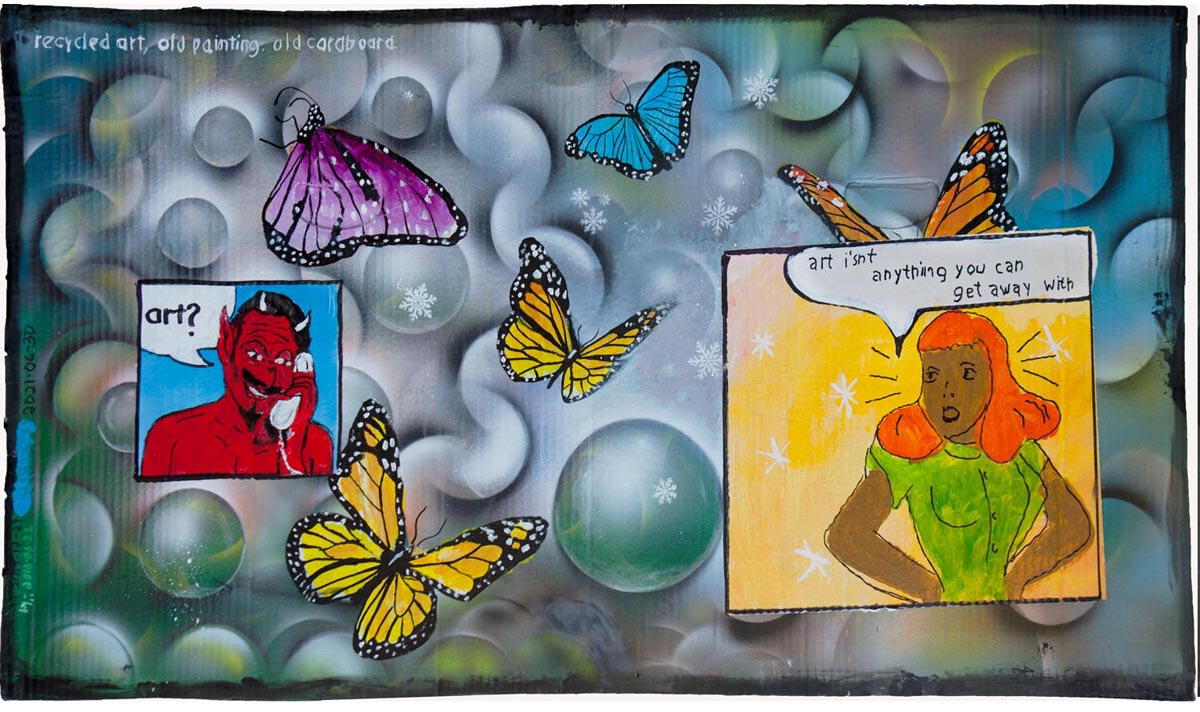

We learn that much of what we call art history was actually marketing by vested interest, while the art theory it gave rise to failed common sense and logic. Realignment is unavoidable. Afterwards we can make of art something worthwhile, rather than anything you can get away with. There's something dubious in having to get away with it. The author expects to convince the reader that there is a fly in the soup.

Consider the art gods.

For the last fifteen years, I have been studying a few well known artists to illustrate a general pattern of contemporary art history. It has taken fifteen years because one who has grown up in a familiar belief system will hardly accept they have grown up believing in lies, but will have an even harder time explaining this to others, the art world, who has created these lies out of the need to have myths to live by. These will be familiar myths which gave us a comfortable and secure paradigm to live with, a sense of meaning that we will not easily surrender even when faced with undeniable contradictions. This article will now present an abridged version of a much larger story with extensive details.

To start,

here is a very different way to see someone like, say, Duchamp. I know we’re supposed to love the urinal and rebel against the system, but today we are the system, so we would be rebelling against ourselves. The semiotic statement of the urinal is that artists piss on art as a rebellion against tradition. Do we really believe that? How often does the reader actually piss on a work of art? Once a week or once a month... or maybe… never?

Before going further, we deconstruct the urinal. Nostalgie de la boue (English: "nostalgia for mud") is a French phrase meaning an attraction to low life degradation.1 The concept presents a rebellion or dissatisfaction with stifling middle class morality, so that the protagonist indulges in the freedom of a temporary rejection of their self-respect. Here this means indulging in a shameful scatology, pissing on art, which stands for an artist symbolically pissing on themselves. Following which the protagonist would feel a sense of freedom, able to return to a restrictive middle class lifestyle after this romp in the dark side.

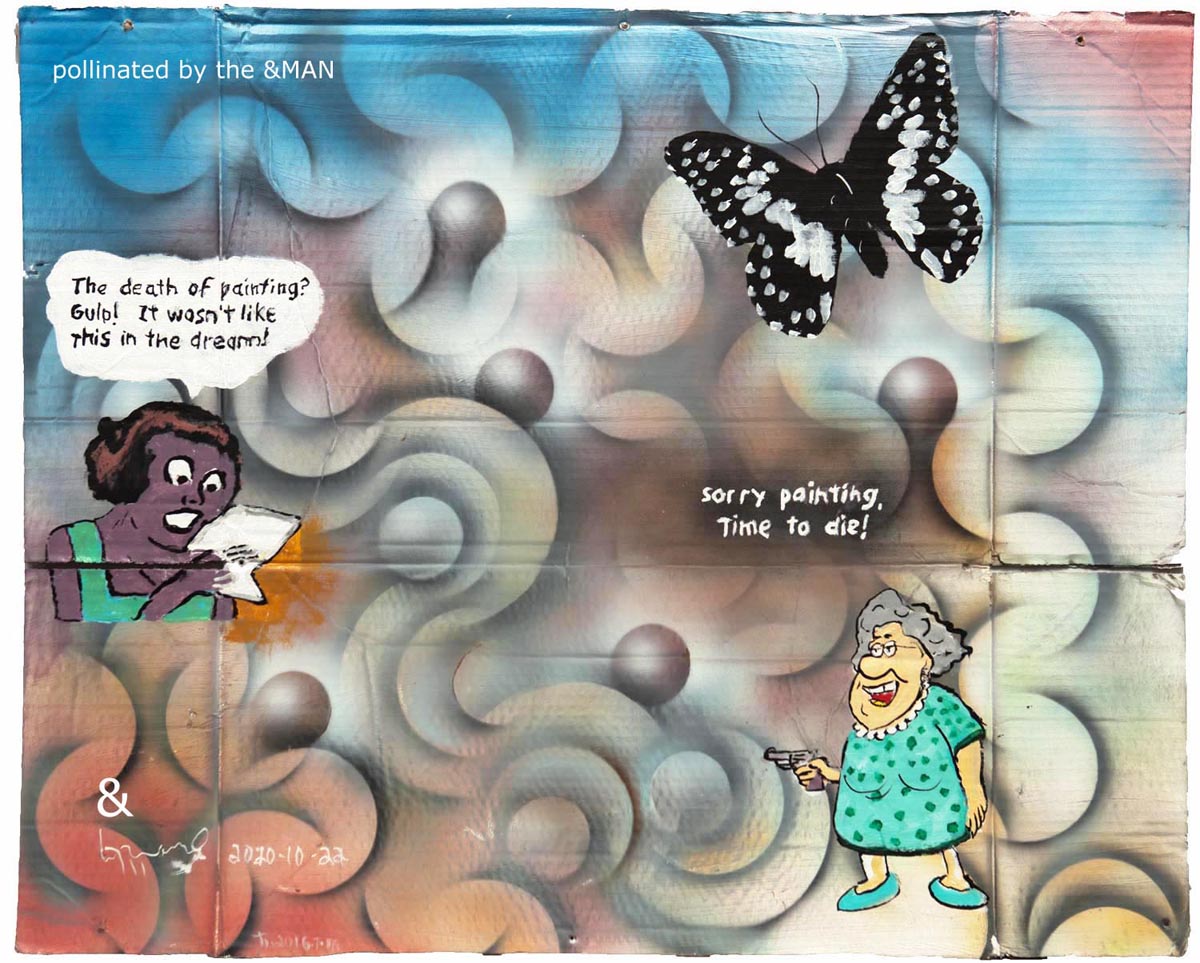

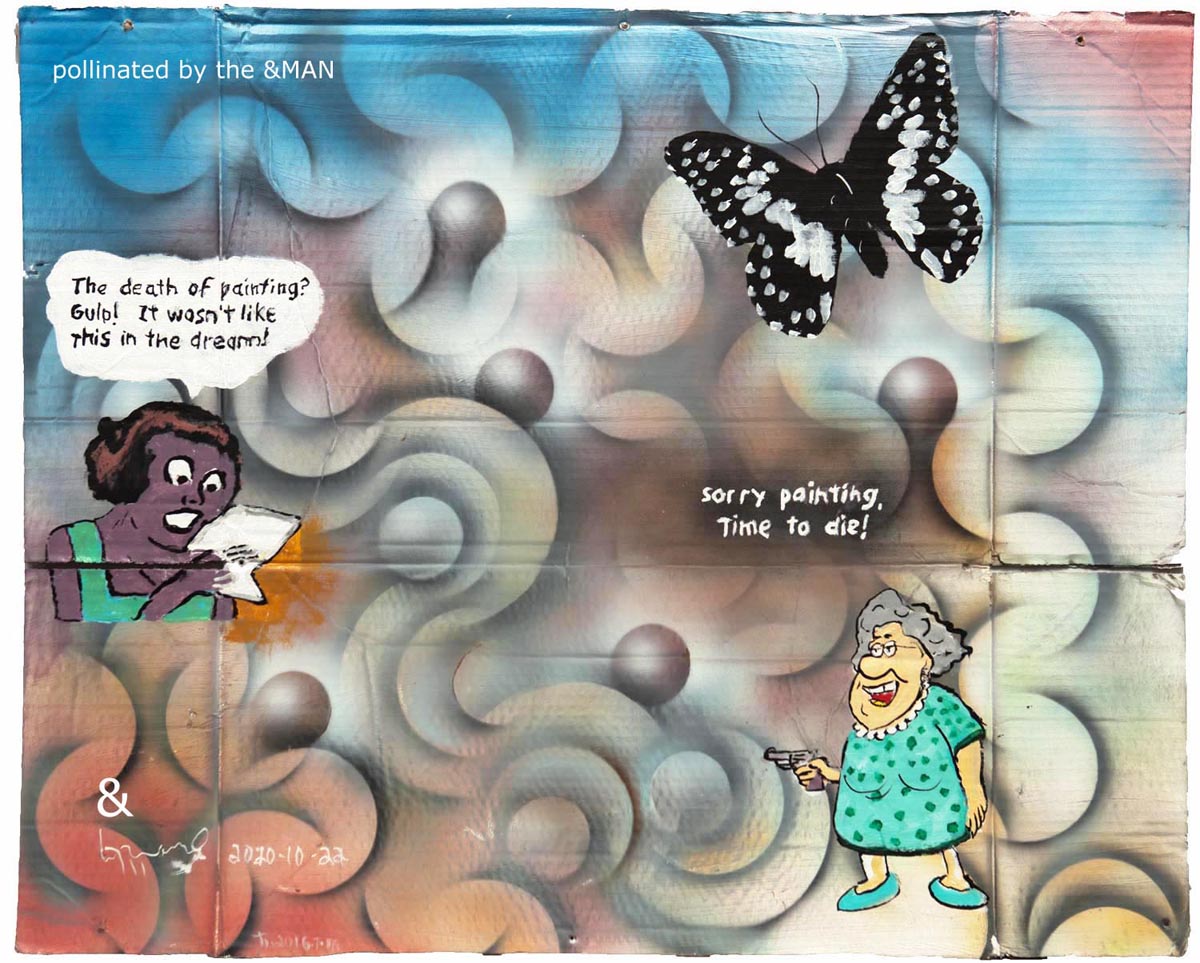

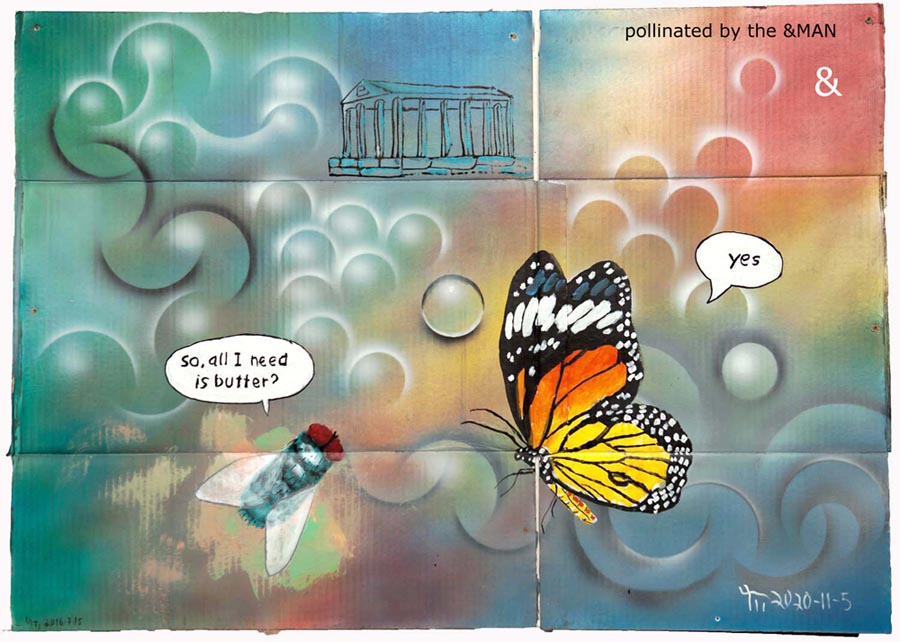

paintings by Miklos Legrady

In such narratives we usually find a cautionary tale like the story of Pinocchio. The psychologist Carl G. Jung wrote of how someone pretending to be insane may fall into the rabbit hole. There would be no adults left in the room. We are warned that acting out his a Nostalgie de la boue may get one stuck in the mud. In Duchamp’s case, we see a DADA strategy of rejecting art, until he came to believe his own press,so that he could no longer be an artist. “It was like a broken leg" he said.2

In 2004 hundreds of British art experts voted a urinal as the most influential art of our time. 3 Marcel Duchamp did not conceive of the urinal, he appropriated it from a syphilitic sociopath, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, to convince the public that art was discredited. Marcel can be heard claiming this in a 1968 BBC interview currently available on youtube.4 He repeated that assertion to seemungly prove we should get rid of art the way some people got rid of religion.

Best kept secret

This could be the art world’s best kept secret, a sacrificium intellectus.What we just saw was a snippet of the full video. In the only copy online, this section, at 17:24/27:09, has been cut out, censored, deleted fromthe video.5 The censored copy, the only onenow available online, was uploaded by curator FrancescaSeravalle. She writes “Interpreting an archive is a matter of patience and intuition, it is above all asking the right questions. It’s about activating a collective memory.” 6 I emailed Ms. Seravalle asking the right question; “why was that section deleted? But she did not reply. Perhap that section linked in the footnotes does not match the collective memory,support the myth. It becomes obvious Duchamp did not understand that visual art was a visual language, that a picture was worth a thousand words.Maybe the science was not common knowledge in his formative years.

After seeing that video, those indoctrinated in the Duchamp myth generally sweep themselves under the rug because of the cognitive dissonance, which would hurt the sensibility of a genuine acolyte. The tendency is to mythify what doesn’t fit, invent invalid excuses and unjustified justification. But it’s too late for that, especially in light of similar evidence included in these pages. We must ask if the reader understands the consequence of degrading culture?

Donald Judd, John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, and Thierry de Duve (Kant after Duchamp) all say that art cannot and should not be defined; art is anything an artist chooses to call by that name. Of course what cannot be defined blends into the background like tears lost in the rain. If art were anything an artist chose to call by that name, such license would corrupt both artist and art world alike. We would be at the mercy of scammers and charlatans. Did DADA create MAGA? When DADA said art was anything Duchamp could get away with, did MAGA reply that politics was anything that Trump can get away with? Did the art world sow the seeds of Donald Trump? Don't say no if the answer is yes.

In 2014 art historian and critic Barbara Rose wrote of Duchamp “I was angry he convinced so many that painting was dead, since above all, I loved painting. I got over this moment of pique because I was intrigued by his imagination and inventiveness. What Duchamp himself had done was always interesting and provocative. What was done in his name, on the other hand, was responsible for some of the silliest, most inane, most vulgar non-art still being produced by ignorant and lazy artists whose thinking stops with the idea of putting a found object in a museum”. 7 And yet such inane art, that makes us roll our eyes in despair, seems to be exactly what Duchamp wanted, since it would obviously discredit art.

Even Barbara Rose did not see that what Duchamp had done was always designed as a DADA gesture to disrespect art. Since no one expected an artist to deny their own field, what Duchamp did was interpreted as an intellectual provocation, when it was really a desire to shock the bourgeoisie for the attention it would bring him. Everyone who had decided Duchamp was an art-loving intellectual who sought to provoke the art world into a greater understanding of art, was fooling themselves, ignoring that Duchamp did say he wanted to destroy art. Such denial was a lot more dignified than admitting a confidence man seeking attention had taken one in. Even Duchamp did not fully realise this, which only becomes obvious after reviewing a lifetime of his assertions. Not only the art world, buyt Duchamp himself, could never admit that his strategy was to avoid the hard work of painting, since shocking the bourgeoisie was a much easier and much more interesting task.

A cult of denial

A definition of "readymade" published under the name of Marcel Duchamp is found in Breton and Eluard's Dictionnaire abrégé du Surréalisme: "an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist." While published under the initials, "MD", André Gervais nevertheless asserts that André Breton wrote this particular dictionary entry.8 Today, in large numbers of peer-reviewed trials worldwide, the artist’s choice consistently failed to elevate common objects to the dignity of a work of art. At the Venice Biennale a pile of trash remained trash for weeks, no matter how often the artist came by to elevate it to the dignity of a work of art. Huffed. Puffed. No art. No dignity.

paintings by Miklos Legrady

In that 1968 BBC interview with Dame Joan Bakewell, Marcel Duchamp repeated his familiar mantra that art was discredited and we should get rid of art like some people got rid of religion.9 But then he adds that he doesn’t know why he wants to do that, and why he remained an artist. It makes sense that Duchamp invented the readymades to dissuade the public from their love of art, although he seems to have been generally unconscious of the finer points of his own process. “The curious thing about the readymade is that I've never been able to arrive at a definition or explanation that fully satisfies me."10 Perhaps he was uncomfortable with the idea that readymades deny the need for an artist while he remained one for decades longer.Hanging a snow shovel on a wall implies that we don’t need artists, since the work is already made. Readymades require no talent and little effort. This concept was similar to a Marxist beliefs that all we can expect of art is an accurate reproduction of reality, re Walter Benjamin. 11

There is a common thread of Marxism among artists in this time, expressed in a belief in the virtues of denying the individual.Duchamp told Pierre Cabane that his choice of Readymades is always based on visual indifference, and, at the same time, on the total absence of good and bad taste. (But that was what Barbara Rose complained his followers were doing ). It was a genuine attempt at a nihilist revolution meant to create a breakthrough by discarding the self, but that did not happen.For him, taste was a repetition of something already accepted.12 In fact, taste is the result of hard won experience.When Duchamp tried to discard taste he was denying the reality of the individual. Taste distinguishes positive values from their opposite.

Ideas should make sense so as not to discredit the speaker. In an interview with Katherine Kuh, Duchamp said, “I consider taste- bad or good - the greatest enemy of art”.13 Elsewhere he states “I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my own tastes..My intention was to] completely eliminate the existence of taste, bad or good or indifferent”.14 That is definitely a Marxist denial of individualvalue.Very popular around that time.

To unpack that we describe taste; sweet and sour, bitter and salt; our taste comes in many flavors, colours, shapes, in style and song; taste is an instinctive judgment expressing our intelligence and our identity through personal choice. Without taste we have no choice, without choice we have no art. Taste is who you are; taste is all you got.

In denying his own taste, Duchamp compromised himself by discarding his uniqueness. This was one of the strategies that destroyed his motivation and killedhis career as an artist. He discovered that you cannot make art without personal judgment.Eliminating one’s own taste allows another’s taste to dictate the narrative, as even found objects already had a designer.

Of course there are inconsistencies to Duchamp’s ethics. Duchamp appropriated the urinal without crediting the original “creator”, his friend Elsa vov Freytag-Loringhoven, except for one letter to his sister.The incriminating evidence was later published by Duchamp’s biographer, Francis Naumann.

“April II [1917] My dear Suzanne- impossible d’écrire. (in the Parisian French of 1917, this meant ‘nothing much to write about’, re Dr. Glynn Thompson.) - I heard from Crotti that you were working hard. Tell me what you are making and if it’s not too difficult to send. Perhaps, I could have a show of your work in the month of October or November-next-here. But tell me what you are making- Tell this detail to the family: The Independents have opened here with immense success. One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture it was not at all indecent-no reason for refusing it. The committee has decided to refuse to show this thing. I have handed in my resignation and it will be a bit of gossip of some value in New York- I would like to have a special exhibition of the people who were refused at the Independents-but that would be a redundancy! And the urinal would have been lonely- See you soon, Affect. Marcel” 15

In Gamboni’s ‘The Destruction of Art’, at the end of his life, Duchamp explained to Otto Hahn “that his readymades had aimed at drawing the attention of the people to the fact that art is a mirage.”. 16Art being very real since the dawn of recorded time, it was the readymades that were the mirage, especially in light of Duchamp insisting found objects are not works of art.“The word ‘readymade’ thrust itself upon me.It seemed perfect for these objects that were not works of art, that were not sketches, and to which no term of art applies.” 17 This thought could be a godsend to museums; they may never recover funds spent on found objects, but they may now be justified in discarding them tofree up valuable storage space.

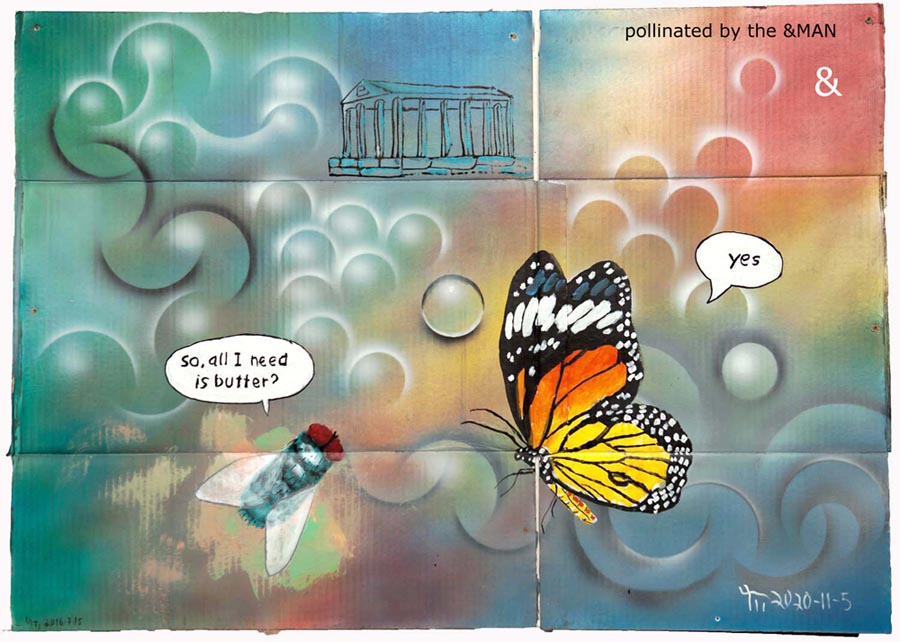

paintings by Miklos Legrady

Duchamp is seen as an intellectual with a deep understanding of art, yet he clearly said in that interview that we didn’t need and should get rid of It. No one who understands art would say such a thing, so why did Duchamp? It does seem he made that statement at first as a DADA tactic to shock the bourgeoisie. His friend Picabia wrote in the Dada Manifesto that art was the opiate of idiots. Psychologists tell us that art has been with us since the dawn of recorded time, and that it is vital in the development of higher consciousness. Denis Dutton, in his Ted Talk “A Darwinian Theory of Beauty”, 18 gives a powerful and convincing argument that art is not an arbitrary social construct, but is grounded in biology and instinct.

How do we reconcile this with Duchamp's lifelong attempts to discredit art? Why did Duchamp say such things? Could Duchamp have been wrong? Or is art really useless and meaningless, and we should get rid of it? In either path, why did the art world keep quiet and is still keeping quiet on what is obviously nonsense andfraud?

Was Duchamp seduced by DADA frivolities that bit the biter? It could have been a DADA strategy to shock the bourgeoisie, but one that he repeated so often that he came to believe it. It may have been the reason he lost his motivation for what he called an unnecessary obsession.Saying art was unnecessary may be why he was paralyzed by an artist's block, and quit art to play chess. "One didn't mean to do it", he told Jasper Johns; "it was like a broken leg". 19

For twenty years, in a room behind his now empty studio, he poked and prodded at Étant donné, once more trying to shock the bourgeoisie, since Étant donné is a vagina seen through a peephole. But the Muse was gone, and like any spurned lover she was not coming back.

Holy Smoke!

Duchamp isn’t the only god wearing a cloak of misinformation. John Cage created amazing works. But his 4’33” aimed to prove that noise was music. No one mentions that he proved that it is not, since we never listen to ambient noise the way we listen to music. Cage also said everything we do is music, which is also false. Were it true, we would not need the word “music”, since we already have the word “everything” to describe everything we do. Cage’s problem is one of absolute statements. His musical experiments are fascinating, and we need only change Cage’s assumptions into questions instead of absolutes. Is everything we do music? Is ambient noise music? Is the act of framing enough to transform an object or sound into a work of art? Then the answers to these questions are not true or false until proven to be one or the other: : they remain valid data, even when the answer is no. Cage’s work is fascinating, as much as his genius for seeing considerations no one else had thought of.

paintings by Miklos Legrady

Among the others whose claims bear rebuttal, Walter Benjamin’s “Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” is the most egregious. Benjamin was a talented lyrical writer.But if you google Benjamin, you will read about a social scientist, an early Marshall McLuhan, who was so prescient he could accurately predict how people in the future would look on art and society. Well, time has been very unkind to Walter Benjamin, as everything he wrote in his 1935 “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” was mistaken. 20 He was writing Marxist Propaganda, since then disproved. For example, “The art of the proletariat after its assumption of power… or the art of a classless society… brush aside a number of outmoded concepts, such as creativity and genius, eternal value and mystery.” Benjamin’s core argument is “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art”, aura referring to the spiritual and emotional effect and effectiveness of art. These supposedly vanish when a work of art is reproduced.

However, our knowledge of art mostly comes from reproductions in books. Books are made by mechanical reproduction yet the power of art and literature is enhanced when reproduction makes the artist or author’s work available to a growing audience.The aura of a work of art is enhanced through mechanical reproduction. Walter Benjamin’s article is a symphony of Marxist propaganda, errors and contradictions. 21 But for nine decades not one person stood up to point this out and correct this misinformation.

Then there’s Sol Lewitt, an amazing visual artist. In the1960's, Lewitt was heralded as one of the fathers of Conceptual art, a hero whose Sentences and Paragraphs on Conceptual Art were published in Artforum. But his Statements and Paragraphs were often questionable.For example, in his opening Paragraphs we read that in Conceptual Art, the idea is dominant; “all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair.22 The person who proved Sol Lewitt was wrong beyond the shadow of a doubt was, of course, Sol Lewitt himself, when he was deeply disappointed in perfunctory executions of his own work. He eventually accepted that everyone has ideas but few have ability. Technique and performance are independent of ideas and therefore it is possible for the non-poet to be inspired and for a poet or painter’s skill to be insufficient to the inspiration.It is skill, the mastery of one’s medium, that turns an idea into a work of art.

So why have we not seen any of this information even though, through the internet, it is now all in the public domain? R.A. Fisher was the founder of modern statistics. In 1947 he was invited by the BBC to talk about science; his words also apply to the arts.

“A scientific career is peculiar in some ways.Its reason d’être is an increase in natural knowledge and on occasion an increase in natural knowledge does occur.But this is tactless and feelings are hurt. For in some small degree it is inevitable that views previously expounded are shown to be either obsolete or false.Most people, I think, can recognize this and take it in good part if what they have been teaching for ten years or so needs a little revision, but some will undoubtedly take it hard, as a blow to their amour propre, or even an invasion of the territory they have come to think of as exclusively their own, and they react with the same ferocity as any animal whose territory is fought over. I do not think anything can be done about it… but a young scientist may be warned and even advised that when one has a jewel to offer for the enrichment of humankind some people will clearly wish to tear that fellow to shreds.”23

Max Planck wrote that science advances one funeral at a time. Or more precisely: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it”. 24

FOOTNOTES

1 Th phrase was coined by Émile Aug, in the 1855 play Le Mariage d'Olympe. Th phrase was coined by Émile Aug, in the 1855 play Le Mariage d'Olympe.

2 Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press

12 Pierre Cabane Dialofue with Marcel Duchamp. p.48 Pierre Cabane Dialofue with Marcel Duchamp. p.48

13 Duchamp quoted by Harriet & Sidney Janis in 'Marchel Duchamp: Anti-Artist' in View magazine 3/21/45; Duchamp quoted by Harriet & Sidney Janis in 'Marchel Duchamp: Anti-Artist' in View magazine 3/21/45;

reprinted in Robert Motherwell, Dada Painters and Poets (1951)

14 Irving Sandler, The New York school – the painters & sculptors of the fifties, Harper & Row, 1978, p. 164 Irving Sandler, The New York school – the painters & sculptors of the fifties, Harper & Row, 1978, p. 164

16 Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art, Iconoclasm and Vandalism, p278, Reaktion Books Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art, Iconoclasm and Vandalism, p278, Reaktion Books

17 Marcel Duchamp Talking about Readymades” (Interview by Phillipe Collin, 21 June 1967), Marcel Duchamp Talking about Readymades” (Interview by Phillipe Collin, 21 June 1967),

in Museum Jean Tinguely, Basel (ed.), Marcel Duchamp, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2002 [exh. cat.]: pp. 37-40

19 Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press.

23 David Salsburg, The Lady Tasting Tea – How Statistics Revolutionized Science. p51, Holt, N.Y. 2001 David Salsburg, The Lady Tasting Tea – How Statistics Revolutionized Science. p51, Holt, N.Y. 2001

|