art statement

Legrady bio

Legrady cv

Legrady's work

on the CCCA

Art Database

National Gallery

of Canada

collection

31works

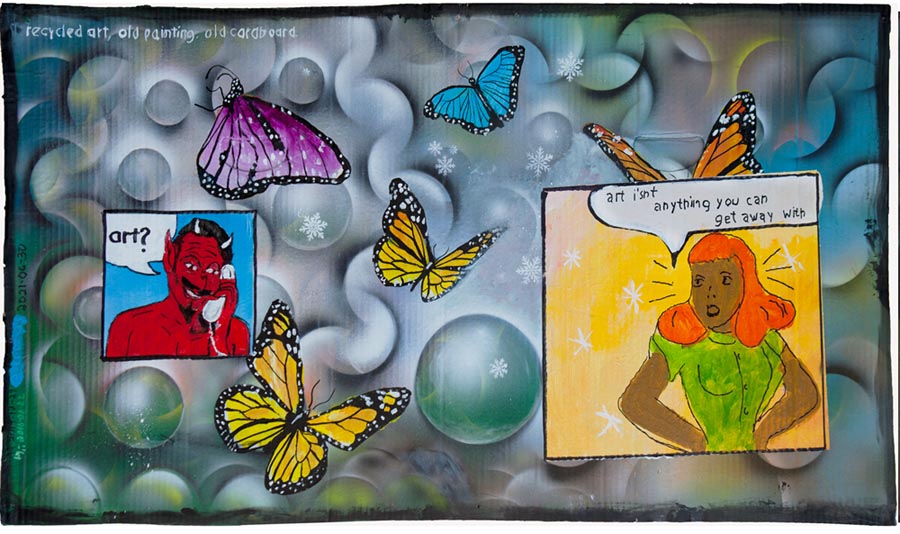

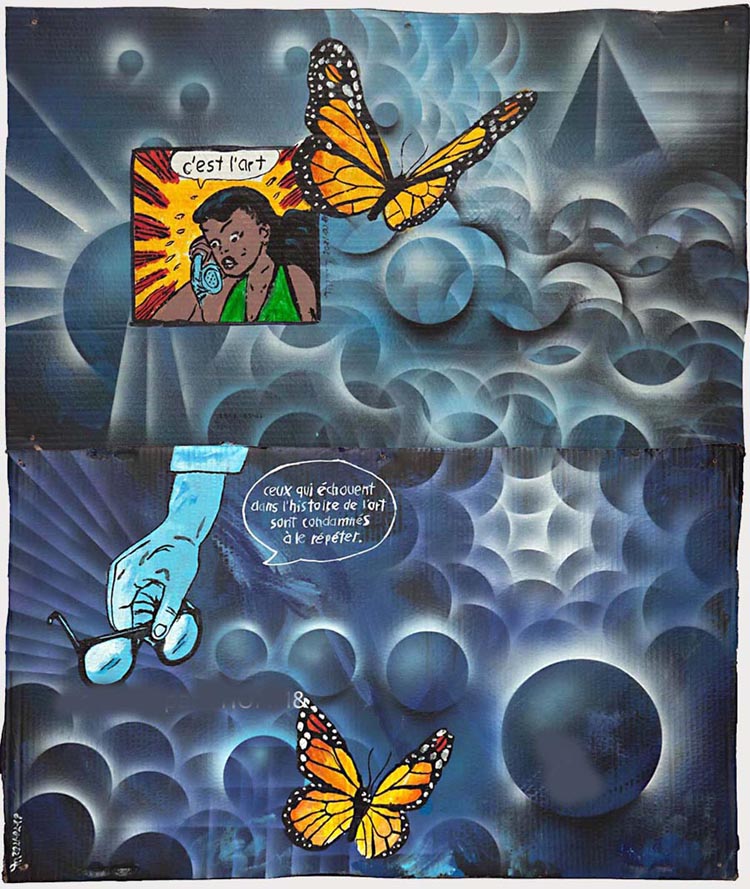

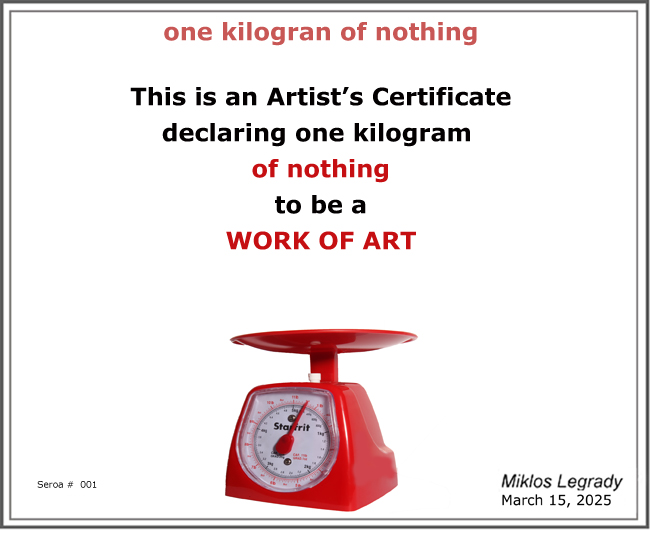

by Miklos Legrady edited by Gabor Podor Neil deGrasse Tyson tells us, in a conversation with Charles Nice, that religion is a mediated experience. “What most people know about their religion is what somebody told them.” Authorities in the field filter religious doctrine; believers are expected to toe the party line (1) The same is true of art, which is as mysterious and perhaps as spiritual as any religion… and just as filtered. Michel Foucault writes, “In every society the production of discourse is at once controlled, selected, organized and distributed” ” (2). American sociologist Herbert J. Gans refers to the “gatekeepers” of the art world. But first, a glance at the past. The word Heretic comes from the Greek hairetikós , an adjective, derived from hairéomai, "to choose”. Heresy originally referred to that period in a youth’s life, usually in the late teens-early twenties, when one explored various philosophies to discover which fitted one best. Such self-directed freedom of thought is obviously anathema in religion, where higher authorities dictate one’s beliefs. Religious faith is a vigorous belief held in the absence of and often in contradiction to facts and logic. The Christian bible, referring to this dichotomy of faith and facts, says that “No one can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the second and despise the first” (Matthew 6:24). Tertullian (c.160-c220), was an early defender of the Catholic Church. He wrote that accepting religious dogma that is overtly and obviously contradicted by facts secured the believer to the belief system. Beliefs in pragmatic impossibilities, such as the son of a god born of a virgin earthly mother, committed the believer to a loyalty that no logic could compel. Tertullian wrote “See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, and not according to Christ.” Col. 2:8. (3) Tertullian further explains; “What indeed has Athens to do with Jerusalem? What have heretics to do with Christians? Our instruction comes from the porch of Solomon, who himself taught that the Lord should be sought in simplicity of heart. Away with all attempts to produce a Stoic, Platonic and dialectic Christianity. We want no curious disputation after possessing Christ Jesus, no speculation after enjoying the gospel. With our faith we desire no further belief. For this is our prime belief: that there is nothing more that we should believe besides.” (4) Of course Tertullian glosses over the fact that he himself, and other Catholic authorities, dictated to the simple hearts what they got to learn of Christ. In the 17th century, Western culture started freeing itself from such religious oppression; there came a modern epistemology; rationalism, Empiricism, and the Age of Reason; Descartes, John Locke, David Hume, and George Berkeley. With René Descartes's “I think, therefore I am", religious faith suffered a critical deconstruction. This is likely why, by the 19th century, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883) that God is dead; he could smell God’s rotting corpse. (5) A shocking thing to say in a more devout era 142 years ago, but he may have been prescient. In a scientific world, religion loses some authority. That religious gap was filled for many who seem to have veered to art as their new spiritual practice. In postmodern art they found the same absolutism embedded in the cultural canon, they found cultural narratives that diverged so widely from documented facts and logic as to assume the irrationality of earlier religious thought. In one example, this author presented a local magazine editor with a critique of Marcel Duchamp’s statement that art was discredited and we should get rid of it the way some people got rid of religion. The editor’s reply was surprising. He recounted how in his youth he had attended a performance where Duchamp played chess in front of an art audience. That event made this editor feel truly embedded in the art history of his time. He concludes that he was not receptive to the current trend of cancelling great figures. If the reader wonders how playing chess is art, or how wanting to get rid of art makes one a great artist, or how scholarly critique is dismissed as an attempt to cancel an artist, we notice the levels of quasi-religious denial that would have made Tertullian proud. For other examples of the obfuscation of art theory, Duchamp has been a great source for deconstruction. He had a talent for painting that reached its apogee with Nude Descending a Staircase, but then he found painting to be hard work and he did say he didn’t like to work. He became a Dadaist, a rebel, as it was easier to shock the bourgeoisie by trashing art than to paint morning, noon, and night. His brand became the attempt to get rid of art using works that suggested art was discredited, such as the urinal, whose semiotic statement says that we artists piss on art. The art world couldn’t believe an artist would disdain their own field, so they assumed Duchamp was an intellectual who rose above their own comprehension, resembling the religious belief that God’s ways are inscrutable to us mere mortals. They never allowed themselves to think Duchamp was pulling their leg and seeking the spotlight by trying to shock them. Another example of the intellectual failure of contemporary art that aligns art with religious worship, centers around a well-known and highly respected journal of aesthetics that had already peer-reviewed a number of my articles but rejected the latest one, on Duchamp. This reviewer said Duchamp could not be critiqued because he has done a number of great works, which the reviewer then proceeded to list. He believed that simply naming those works was sufficient proof Duchamp was above criticism and so rejected my article. The magazine editor defended the reviewer by saying he was a highly esteemed colleague whom the editor would not offend. The university is kin to the religious organizations in that networking trumps scholarship. I contacted the founder of that journal, who wrote that he himself had published a book on Duchamp, which he advised me to read. He said he never pays attention to what the artist says or writes but simply looks at the work, and Duchamp’s work was enigmatic, mysterious, fascinating and incomprehensible. I replied that if we read Duchamp’s Dadaist statements, the works become easy to understand, as he was simply trying to shock the bourgeoisie. The professor replied with a stiff upper lip, saying “we have a difference of opinion.” Letter for letter, word for word, chapter for chapter the art world parallels religious mindsets, revealing how art became a perfect substitute belief system following the death of god, whose corpse still emits a dastardly smell. But of course most cultural aficionados fail to notice their own solipsism. They listen to the authorities and learn a simple art history that filled their need for cultural mysticism. Wait… what? How could this be? Art used to be the realm of creative and talented individuals, even when their work served the upper classes. When did it become the realm of devoted believers? When was art institutionalized? Robert Storr was a curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At a Dia Conference in 1969, he said that during the 1960s, art moved from the Cedar Tavern to the Seminar Room.l (6) When art entered the academy and was institutionalized under the control of the gatekeepers, things changed. Previously, artists were judged by vision, skill, quality, the beauty that made their product desirable. That is no longer the case in a postmodern era. A few years ago, National Gallery of Canada curator Kitty Scott wrote on Facebook that no one knows what art is anymore. Which should really prompt us to make an effort to find out, since every other profession knows what they are doing. In this paper, we draw a wide circle to flesh out how art became a religion, a recent transformation from its original purpose. In his 2017 presentation, titled Modern Art; The Goldsmiths' Company Lecture, historian David Starkey (7) tells us that Art, in the sense that it is used today, was previously unknown. The liberal arts in the 16th century were the arts that were taught in the universities; grammar logic, rhetoric, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, music, all of that was well known, but there was nothing we would call the arts. There is this distinction between the liberal and the sordid. The Liberal arts were the abstract intellectual activities, the work of the mind that liberated the privileged from manual labour. Sordid then meant work made by hand, by the working class. According to Starkey, the concept of art as we understand it today, was invented by one man, Vessario, in his book The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, first published in Florence in 1550. Vessario equally invented the term "the Renaissance". According to Starkey, Vessario also invented the concept of the supremacy of the arts in the Roman period and revived in the Renaissance. Starkey tells us Vessario sought to elevate one art above all others, the art of painting. Vessario impressed on his readers that the painters whose lives he describes were all well versed in the liberal and abstract arts, thus raising painting above the manual level of the Sordid arts. (8) Of course, Marcel Duchamp undid Vessario’s work with his claim that painting was dead, eventually saying art was discredited, we should get rid of it. Duchamp was very clear in stating his Dada views meant to shock the bourgeoisie. He said he wanted to destroy art. There is a 1968 YouTube video shot a year before he died, Joan Bakewell interviews Marcel Duchamp for BBC’s Late Night Line Up series in which Duchamp talks about after his early career, after the Large Glass, when he stopped painting, and he decided that art was unimportant to him or to culture, art was discredited, it was an unnecessary adoration, and we should get rid of art the way some people got rid of religion. (9) Duchamp’s concept of the artist as a rebel and an intellectual was idealized from 1945 on, when universities and art schools opened in large numbers following World War 2, as the G.I. Bill gave all white veterans, but not soldiers of color, the right to a free university education. According to historian Ira Katznelson, "the law was deliberately designed to accommodate Jim Crow.(10) This was finally amended during the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s The 20th and 21st Century The postmodern canon spotlights contemporary art’s resemblance to religion. The gatekeepers, authorities all, remind us that most fine arts producers graduate from similar schools and share the same values, which are reflected in their association, their production, and the systems created thereby. Surely a cultural blindness results from such group judgments. When a bad idea enters such an academic body, it spreads like a virus. Painting, sculpture, and other classic art forms required decades of study starting in childhood, and then constant practice; the arts were a “use it or lose it” proposition. But in the postwar art world, artists no longer earned a living making art but by teaching. By the 1980s one attended art school expecting a teaching job on graduation. Sadly, teaching is so consuming there is little time left for studio work. A teacher must prepare and deliver classes, grade papers, meet with students, with parents, attend faculty meetings, fundraise, so a new art paradigm was invented which echoed the past glory of the Liberal abstract arts. The academy moved the goalpost because there was so little time for artists to keep up their practice. Art was now to be intellectual so conceptual art came into being. Duchamp, who had never understood that the various art media consisted of non-verbal languages, and therefore wanted art to be intellectual, became the deity of the new academic art regime. In 2004, five hundred British art world professionals voted the urinal called Fountain the most influential artwork of the 20th century, in spite of Duchamp’s statement that it was not art. Who would have thought scatology was so sexy? Duchamp’s urinal is generally acknowledged to be a great work of art, even though Duchamp had stated that“The word ‘readymade’… seemed perfect for these things that weren’t works of art, that weren’t sketches, and to which no term of art applies.” (11) ““Most influential “does not mean the best or even a great work, yet most people will assume if it’s most influential it must rank among the great. Here we’ll adapt Neil deGrasse Tyson’s words; “Art is filtered by the authorities in the field”.  Art is just like religion; a spiritual experience, if the art is good enough. We have to qualify art at the moment because at one time, art meant our highest achievement, a mastery higher than a professional standard, as seen in such expressions as “the art of medicine” or “the art of conversation.” But in the 20th and 21st centuries, where we have defined the art of our time as a postmodern version of “shocking the bourgeoisie”, as being rebellious, the most rebellious thing we could do is to make bad art. This bad art we would define as the best art of our time, since it was most effective at shocking the bourgeoisie. This is no superficial or glib statement: bad art has been the rage for decades. In 2003 Jerry Saltz wrote, "All great contemporary artists, schooled or not, are essentially self-taught and are de-skilling like crazy. I don't look for skill in art.” (12) In the 1960s Susan Sontag even suggested boring art was perfectly valid.(13) Today our pundits tell us “beauty is out”. However, Nobel physicist Paul Dirac said “when I see beauty in my equations, I know I’m one the right path to progress”, a statement Einstein agreed with. We should question if the beauty algorithm only applies to science, if it’s no longer valid in the fine arts, because if that is the case, ugliness is our other option. Has anyone ever said “when I see ugliness in my artwork, I know I am on the right path to progress?” Since the dawn of human existence, many have experienced a spiritual awareness for which they sought explanation. Religion is the precursor to science. Neil deGrasse Tyson talks about “the God of gaps”, God being an explanation that filled gaps in our knowledge. As an example, in physics, specifically classical mechanics, we calculate planetary orbits using Newton's laws of motion and Newton's law of universal gravitation. However, Newton found that when Earth was closest to Jupiter, which even then was very far away, the mass of Jupiter was still large enough to slightly nudge Earth out of it’s calculated orbit. Newton worried this meant the solar system planetary orbits would eventually be pulled apart. He finally decided the solution was that every now and then, God steps in and rearranges things. Two hundred years later, Lagrange and Laplace were the first to advance the view that the so-called "constants" which describe the motion of a planet around the sun, gradually change. They are "perturbed", as it were, by the motion of other planets and vary as a function of time; hence the name "perturbation theory". The gravitational pull of different planets kept their orbits stable. The Emperor Napoleon, who was interested in science and read as much as he could, went to visit LaPlace. During their conversation, Napoleon asked LaPlace why the scientist did not mention the Great Architect, meaning God? LaPLace replied that he had no need for that hypothesis. Was art the perfect substitute? Since there is no God figure in art other than some artists we elevate to tall pedestals,, art may have beans a perfect substitute for religion and the illogical mysticisms we unconsciously sought in order to explain the creative unconscious. And yet… “The criterion we use to test the genuineness of apparent statements is the criterion of verifiability”, so Oxford’s A.J. Ayers writes in a study of language, truth, and logic. “We say that a sentence is factually significant to any given person if, and only if, they know how to verify the proposition it purports to express” (14)We now question if this applies to the fine arts, as many believe that art has no pragmatic effect. Perhaps our first step will be to prove that it does. While some cultural workers believe that art has no consequence, political science suggests your culture is your future. When DADA said art is anything Duchamp can get away with, MAGA replied that politics is anything that Donald Trump can get away with. Our culture is our future. The answer to such illogical outcomes in art and politics may be to define our terms, to define what we call art. Seeking such definition, we might agree that art consists of non-verbal languages, which express that which cannot be put in words. There is body language, whose formal aspect is dance and performance. Acoustic language, whose formal aspect is music. Visual art, where a picture is worth a thousand words. This non-verbal quality applies even to literature which differs from writing in that literature is expressed in the tone, the octave, the tempo, the mood of that which is written. Such non-verbal elements universally engage our feelings in ways that a purely objective fact may not. Judgments - quality When we experience works of art in any medium we are always faced with questions of judgment, we judge the work on a spectrum from excellence to mediocrity. In the late 20th and early 21st century, we are also faced with a definition of art. Donald Judd, Marcel Duchamp, and Thierry de Duve all wrote that art cannot and should not be defined; art is anything an artist chooses to call by that name. Of course what cannot be defined is lost to the background like tears lost in the rain. If art was anything an artist chose to call by that name, such irresponsible license would corrupt both artists and art world alike. We would be at the mercy of scammers and charlatans And of course religion has been filled with scammers and charlatans, yet people still turn to religion? For the same reason we turn to art, hoping to find fewer scammers and charlatans, to find meaning in the least material and most abstract statements that fill out existence. Artists speak of being driven by an urge for discovery of the non-verbal spirit within themselves, the products of the unconscious, the Eureka principle. This inner voice is fascinating to those with the ability to experience it. Nor should we ignore the practice of art, a continual self-improvement, a mastery of the media we work with, and so a mastery of our own language that we think with. For many who can no longer believe in a God in Heaven, a God of the gaps, knowing that science will eventually fill those gaps, for such people as for so many others there is still the knowledge of a spirit of inspiration, the creative unconscious. There are so many unknowns about our mind, as the very notion of consciousness posits there is an unconscious part of the mind. Of course there is, if we consider the mechanisms that direct our chemistry and over which we have no control and of which we have no awareness, the unconscious within. When art became a religion it most likely failed its mandate. Before, art preached and convinced through the non-verbal statement inherent in the artwork. Once art became a religion, it convinced through communal beliefs as defined by the gatekeepers, giving participants a sense of belonging that established religions provide. In prehistoric times art was both an enhancement, a decoration of our bodies, tools, clothing, and homes. It was also magic, bringing the power of the spirits and the spiritual to our human realm. Over time we see how art established cultural styles, expressed our identity. Eventually, at the turn of the 20th century and the age of science and psychology, movements such as the impressionists et all deconstructed the visual language of art, a deconstruction that went on through to pop art and the abstract expressionist modalities. But following the first World War came DADA, a rejection of the culture that created such horrors as that war. Picabia expressed this rejection in his DADA manifesto when he wrote that art was the opiate of idiots. Duchamp openly said that he found painting too hard and he hated hard work, had never worked a day in his life, therefore painting was dead and the urinal expressed how we feel about art, we piss on it. Duchamp did not like to work. Donald Kuspit wrote of Matisse out-performing him. (15) “Basically I’ve never worked for a living … Also I haven’t known the pain of producing, painting not having been an outlet for me, or having a pressing need to express myself. I’ve never had that kind of need – to draw morning, noon, and night.”(16) Sol Lewitt and the 1960s Sol Lewitt followed up with his Statements and Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, 1967, published in Artforum. He said the idea was dominant, the execution was but perfunctory. The he found himself deeply disappointed at perfunctory executions of his own work. He came to understand that it was motivation, skill and effort, the execution of the work that turns ideas into art. But he never revised his writing, which had been published in Artforum. We only learned this in 2019, when Larry Bloom published his biography. . (18)For fifty-two years students were told that while the idea was worthwhile, skill and execution were superfluous. Those students became the next generation of teachers who spread that misinformation. In the 21st century, after it was announced that art was neither about aesthetics or beauty, the postmodern modality made art political or intellectual, neither of which suited the human spirit that first gave rise to the arts. But since art had been academically institutionalized, it could not be simply dispensed with. Too many members of the public had already adopted art as a religion, so they gathered at openings and lectures for a communion of spirit. But this was no longer art, it was a religion. And so we turn from our earlier proto-religion to this knew religious territory, but it is not without problems. The Banana Art became a way to express one’s wealth and power, just as St. Peter’s Basilica and the Vatican in Rome had in the past. The art culture became a set of realities and myths, truths and fallacies, as bizarre as the contradictions of religious faith. Moses, or was it Marizio Cattelan , came down from the mountain and found his people worshipping a golden urinal. The urinal was then stolen, as thieves broke into Blenheim palace and ripped the urinal out of a bathroom right beside the bedroom where Winston Churchill was born. Art has become a golden toilet, then a banana worth at first $125k, a figure that soon rose to $6 million... Yet was it worth that much? When performance artist David Duna rushed into Cattelan’s exhibition space at Basel Miami, tore the banana off the wall and ate it, Cattelan did not call for a stomach pump to retrieve his valuable property. He knew it was not worth the asking price though he had sold three certificates at that show. A few years later he sold another certificate to a Korean Bitcoins merchant for $6 million U.S. Once again we need to rebel, this time against an art world that so debased itself that taping a banana to a wall is worth $125k. “The modern artist must understand group force; he cannot advance without it in a democracy.” (19) We see how art provides religious mysteries, the magic of believing in the illogical and unbelievable. Yet if we keep on this way, soon nothing in this room will be seen as a work of art  https://legrady.com/concept/idea/index.html Footnotes 1  Neil deGrasse Tyson and Chuck Nice, Does the Universe Need a Creator?, youtube video. Neil deGrasse Tyson and Chuck Nice, Does the Universe Need a Creator?, youtube video.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1o2NaiNlvPQ 2  Rachel Adams, Michel Foucault: Discourse, 2017 Rachel Adams, Michel Foucault: Discourse, 2017https://criticallegalthinking.com/2017/11/17/michel-foucault-discourse/ 3  Tertullian: Defender of the Faith, The Genovan Foundation, 2024 Tertullian: Defender of the Faith, The Genovan Foundation, 2024“As a young man growing up in Carthage, Tertillian received a superior education in rhetoric, literature, philosophy, Latin, and Greek. Once he became a Christian in his late thirties he put all of that knowledge to use in defending the faith.” https://ttsreader.com/player/ 4  Tertullian, On the Prescription of Heretics, 7; quoted in Lane, A Concise History of Christian Thought, 16-17. Tertullian, On the Prescription of Heretics, 7; quoted in Lane, A Concise History of Christian Thought, 16-17.5  The Project Gutenberg, Thus Spake Zarathustra, by Friedrich Nietzsche The Project Gutenberg, Thus Spake Zarathustra, by Friedrich Nietzschehttps://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm 6  "Invisible Ink: Art Criticism and a Vanishing Public," sponsored by Art Table and "Invisible Ink: Art Criticism and a Vanishing Public," sponsored by Art Table and the American chapter of the International Association of Art Critics at the American Craft Museum on May 15, 1996. http://www.studiocleo.com/cauldron/volume3/confluence/miklos_legrady/text/storr.html 7  Starkey has since been exposed for shameful racisms, which means we cannot read his work innocently Starkey has since been exposed for shameful racisms, which means we cannot read his work innocentlyThe author and editors ensured there were noracist influences in the passages quoted here, 8  David Starkey - Modern Art; The Goldsmiths' Company Lecture David Starkey - Modern Art; The Goldsmiths' Company Lecturehttps://youtu.be/5oenp21aFAM?si=NsJnRQ8U9CngM840&t=934 9  1968 BBC interview with Marcel Duchamp where Duchamp says we should get rid of art. 1968 BBC interview with Marcel Duchamp where Duchamp says we should get rid of art. https://youtu.be/Zo3qoyVk0GU?si=bYdw47iUJ7CsWK8h 10  Bolte, Charles; Harris, Louis (1947). Our Negro Veterans, Public Affairs Pamphlet No. 128. Bolte, Charles; Harris, Louis (1947). Our Negro Veterans, Public Affairs Pamphlet No. 128.11  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A window into something else, p48, Da Capo Press Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A window into something else, p48, Da Capo Press12  Jerry Saltz, Seeing Out Loud, Publisher : The Figures 2005, Jerry Saltz, Seeing Out Loud, Publisher : The Figures 2005, 13  Sontag wrote confused contortions on postmodern artists, possibly in an effort to justify the unjustifiable. Sontag’s quote reads: “People say ‘it's boring’ - as if that were a final standard of appeal, and no work of art had the right to bore us. But most of the interesting art of our time is boring. Since art has always been our highest achievement, we can all agree that being boring does not meet that standard, is not our highest achievement. MARIA POPOVA, Susan Sontag on the Creative Purpose of Boredom, marginalianhttps://Ww.themarginalian.org/2012/10/26/susan-sontag-on-boredom/ Sontag wrote confused contortions on postmodern artists, possibly in an effort to justify the unjustifiable. Sontag’s quote reads: “People say ‘it's boring’ - as if that were a final standard of appeal, and no work of art had the right to bore us. But most of the interesting art of our time is boring. Since art has always been our highest achievement, we can all agree that being boring does not meet that standard, is not our highest achievement. MARIA POPOVA, Susan Sontag on the Creative Purpose of Boredom, marginalianhttps://Ww.themarginalian.org/2012/10/26/susan-sontag-on-boredom/ 14  A.J.Ayers, Language, Truth and Logic, p48, Pelican Books A.J.Ayers, Language, Truth and Logic, p48, Pelican Books15  Francis M. Naumann and Donald Kuspit, Duchamp: An Exchange, Artnet Francis M. Naumann and Donald Kuspit, Duchamp: An Exchange, Artnet http://www.artnet.com/magazine/FEATURES/naumann/naumann6-15-11.asp 16  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, I live the life of a waiter, p95, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, I live the life of a waiter, p95, Da Capo Press. 17  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press.18  Larry Bloom, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, Wesleyan University Press, 2019 Larry Bloom, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, Wesleyan University Press, 201919  Jane Heap, in a review of the Independents’ show, The Little Review, Winter 1922 Jane Heap, in a review of the Independents’ show, The Little Review, Winter 1922 |