art statement

Legrady bio

Legrady cv

Legrady's work

on the CCCA

Art Database

National Gallery

of Canada

collection

31works

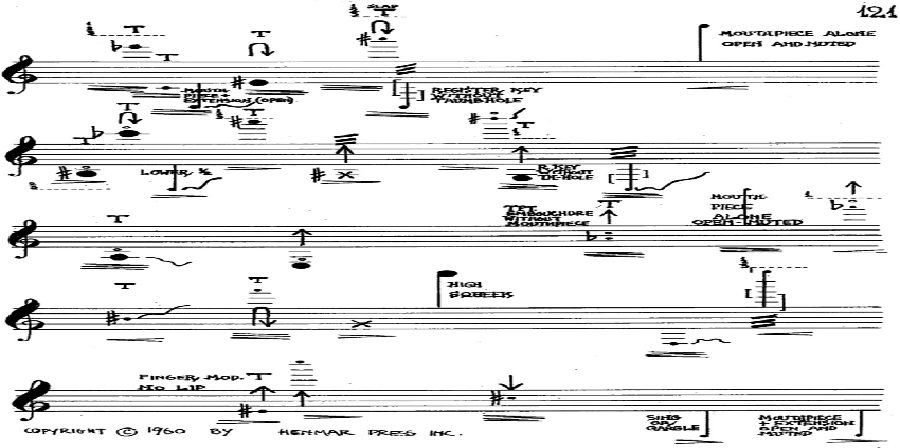

John Cage: Concert for Piano, Solo for Clarinet (p. 121) Edition Peters No. 6705-CL © 1960

by Henmar Press Inc. New York. Reproduced by kind permission of Peters Edition Limited, London.

John Cage

By Miklos Legrady,

edited by Gabor Podor

The purpose of deconstruction is to locate hidden flaws, ambiguities, and paradoxes of which the author is probably unaware. Derrida’s method of deconstruction was to look past the irony and ambiguity to the layer that genuinely threatens to collapse that system, so we will follow that model here, though we start with a taste of the irony and ambiguity.

Consideration of the theme

Why do we believe some things when they are demonstrably false? Because that is the nature of group dynamics; when sharing common beliefs, disagreement risks alienation. Then how can we correct such errors? Physicist Max Planck wrote that science advances one funeral at a time. Or more precisely: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it”. It is probably time to review John Cage, as this adage applies to the arts as much as to science.

John Cage’s experiments with sound mark him as one of the great artists of his generation. This current critique does not doubt him but it does light up both his insights and misconceptions. I am not here to downplay Cage, whose talent is obvious. But I am here to chastise an art world failing at language, truth, and logic, which this art world seems to purposefully ignore in order to deify talented artists that are as liable to error as every other human being.

For exampple, Sol Lewitt wrote in Artforum (1)) that in conceptual art the idea is dominant while the execution is perfunctory. But then he was disappointed in perfunctory executions of his own work, yet never revised his writing. It would have been embarrassing, after being published in Artforum. We only learned this when Larry Bloom published Lewitt's biography(2), in 2019, which means that for 50 years, universities propagated the news that skill was unimportant.

In fact, skill consists of a mastery of the media, therefore ia skill in clarity of its messaging. When your statement is unclear, your message is confused. And so, believing that the idea was the dominant aspect of a work of art, in the year 2019, at Basel Miami, three certificates sold for $125,000 each attesting that a banana was a work of art. As reported in Wikipedia, ‘Comedian is a 2019 artwork by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan. Created in an edition of three (with two artist’s proofs), it appears as a fresh banana duct taped to a wall. As a work of conceptual art, it consists of a certificate of authenticity with detailed diagrams and instructions for its proper display.’ Had Cattelan believed that his banana was worth $125,000, when performance artist David Duna rushed in and ate the banana, Cattelan would have called for a stomach pump to retrieve his valuable property. That Sol Lewitt or John Cage also made mistakes does not disparage the greater good of their work.. But the consequences of theirs mistake expand in concentric waves. Once the cat is out of the bag, who knows what disasters will follow? For example, in 2025 this very author produced an artist certificate stating that 1kg. of nothing, in this room, was a work of art(3)

John Cage

He is not a traditional musician whose works aimed at acoustic attraction. He may even be better described as an acoustic artist who experimented with the extremes of sound. Some successful, others questionable and open to criticism. Cage may well fall under the category of 20th century nihilist artists whose work found no criticism as it was barely understood in his own time even as it gathered much interest for it’s experimental progress. But we may well call him an acoustic artist rather than a musician, when compared to Mike Oldfield or Phillip Glass.

Mike Oldfield’s work is beautiful; one may listen to Tubular Bells for hours as it is so enticing. Music comes from the muse, as the etymology of music comes from the Greek mousiké techn? (“art of the Muses”), named after the Muses, goddesses of arts and sciences, via Latin musica and Old French musique, entering English around the 1300s to describe ordered sounds, poetry, and the sciences, displacing older English terms like dr?am. Note that the etymology refers to”ordered sounds”. Physicist Paul Dirac said that “when I find beauty in my equations, I know that I am on the right path of progress”. No one said the same applies when they find ugliness in their work, yet beauty is disparaged in the late 20th and early 21st century art paradigm. John Cage was one who shares responsibility for the word ‘beauty’ no longer being found in a description of music. A mistake, for beauty attracts while Cage’s work does not depend on attraction. It interests us but one would not listen to any of Cage’s works more than once for its acoustic content. Beauty attracts but its counterpart is ugliness, repulsion, boredom. One approaches the later out of curiosity, or scholarship, but rarely repeats the experiment, unlike music, to which we listen repeatedly.

Cage is famously quoted as saying, “There’s no such thing as silence,” a concept central to his iconic conceptual work, 4′33″. Cage argued that perceived silence is actually filled with ambient sounds, from wind to human bodies, and that these accidental sounds constitute the true music of the piece, encouraging the listener to be mindful of their surroundings. His experience is based on time spent in an anechoic chamber, where he could still hear the sounds of his own circulation.” There are times when we should be conscious of our surroundings, and at those times we generally are aware of either dangers, or beautiful sounds around us. There are other times we have more important things to thing about. But Cage’s assumption is a moot point. It is based on his idea that ambient noise is music, the music of the universe and of the human body. However, there is no music of the universe or the human body, for none of these are intentional.

John Cage’s extremism and experimentation propelled him to worldwide fame, but he also held mistaken assumptions which no one dared question. For example, although he denies it, there is such a thing as silence. Silence is the absence of intentional sound, the space between ordered sounds.. Silence separates musical passages to give the mind time to absorb the theme, and if someone should cough or move their chair in the audience, no one believes such ambient sounds are part of the artist’s musical intentions unless clearly stated. And then we must ask if that sound is worthwhile listening to, we must judge if it is good art.

Design Guild Heroes: John Cage. The Design Guild.

Music is always an intention. Even when including accidents and chaos, which are allowed consciously; the musician is aware of their selection. When that is not the case, when the musician records anything and everything without judgment, the work has nothing more to tell us than repeating the bare facts of its existence. For what we seek in art is the artist’s judgment. Ambient noise contains no art, skill, inspiration or effort. There is no consciousness present in accidents, nor any artist’s statement. Ambient sounds simply informs us of our environment, contributing pleasurable sounds or warnings of dangers. Art means a mastery of media to express an intention based on an artist’s vision. The absence of the artist is neither a stroke of genius, nor a brilliant inspiration. A painter who locks the doors of a gallery for the length of their show obviously has nothing to say, they are impotent. An artist’s absence is not a statement; it is a denial, of no importance when referring to art, except among nihilists. For Cage it’s different. His exploration of the edges was worth the effort, but it does not seem he learned the right lessons from this one, though he produced other works that merit admiration.

Once intention is taken into account, silence is the space between two intentional sounds. The space between two unintentional sounds, on the other hand, is always filled with other unintentional sounds. To gape, open mouthed, at any utterance without judging what is being said, reveals a critical failure on the part of an audience of supposedly the most intelligent scholars in the art world.

Cage’s stature brought credibility to everything he said, right or wrong. We, his heirs, need to know which is which. John Cage’s composition RGAN2/ASLSP – As SLow aS Possible, consists of eight pages of music performed as slow as possible. The first note was played on an organ in St. Burchardi church in Halberstadt in 2001. The next note was played on February 5, 2024. The next chord change for John Cage’s As Slow As Possible will be performed August 5, 2026. The following chord will be on October 5, 2027. This acoustic work is due to end in 2640.

This work is conceptually linked to astronomer Enrico Femi’s paradox (“Where is everybody?”), concerning the existence of aliens. One problem is the length of time a message would take to reach another galazy. A signal we send out might travel 80 light-years to reach a galaxy with a civilization able to understand it, and their reply would take another 80 light-years to reach us, which means 160 years between signal and response. Cage’s ASAP touches on this theme.

|

However, another of John Cage’s work, 4’33” is not a musical work but an open question, and it is only a failure when Cage expressed it by saying that ambient sound is the music of the universe. More on this later. Music, like all art, is always an intention. The intention here fails because we do not listen to ambient noise as we do to music. Ambient noise informs us of environmental physics, music informs us about the musicians soul and spirit. Music is a conscious statement, ambient noise is not a statement, it is an acoustic residue. So we do not listen to 4’33”aswelistentomusic,thereforitisnotmusic,oftheuniverseorourbodies.

John Cage was also mistaken when he said that everything we do is music. If everything we did was music, then nothing we do would be music; the term would cease to exist. There would be no need for a word like music if it does not describe something which differs from everything else. We already have a perfectly good word we call ‘everything’, which we use to describe everything. Linguistic classes exist to express pragmatic differences. If all words have the same meaning, then thoughts, ideas, and communication come to an end. Hannah Arendt wrote if men were not distinct…they would need neither speech nor action. (4)

Kyle Gann own's work presents a mastery of composition and performance (5) on the opposite end of the spectrum, so perhaps his appreciation of Cage shows a mind open to diverse philosophies. He wrote about John Cage’s 4’33” of silence that “it was a logical turning point to which other musical developments led. For many, it was a kind of artistic prayer, a bit of Zen performance theater, that opened the ears and allowed one to hear the world anew. To Cage it seemed, at least from what he wrote about it, to have been an act of framing, of enclosing environmental and unintended sounds in a moment of attention in order to open the mind to the fact that all sounds are music." This author disagrees, music is made by selection, by choice. All sound is obviously not music.

One story about Cage recounts his sitting in a restaurant with the painter Willem de Kooning, who, for the sake of argument, placed his fingers in such a way as to frame some bread crumbs on the table and said, “if I put a frame around these bread crumbs, that isn’t art”. Cage argued that it indeed was art. The question then becomes ‘is it any good as art, since it is exactly the same as everyone else’s framing?’ Framing something does not create a work of art, rather it is the opposite. We frame a work of art to preserve the work and display it. That which is shown must be worth showing. To assume it is valuable because I show it, that is vagrant solipsism.

Kyle Gann also wrote, “certainly, through the conventional and well-understood acts of placing the title of a composition on a program and arranging the audience in chairs facing a pianist, Cage was framing the sounds that the audience heard in an experimental attempt to make people perceive as, art sounds that were not usually so perceived. One of the most common effects of 4’33”, possibly the most important and widespread effect, was to seduce people into considering as art phenomena that were normally not associated with art. Perhaps even more, its effect was to drive home the point that the difference between Art and Non-art is merely one of perception, and that we can control how we organize our perceptions. (6)

Again this author objects. We do not judge or experience art by organizing and controlling our perceptions. That is a Marxist error promoted by Walter Benjamin.(7) ambient phenomena is not art but nature. Nor is art sensation and observation but transformative statements involving a unique vision expressed with skill and effort. As Sol Lewitt learned, that is the difference between art and juvenilia.

The truth is that everyone who attends 4’33” soon gets bored. Accidental noise does not fascinate us for very long, while amazing art does. Yes, we can control ourselves and stay seated, but such disappointment is not the point of art. Shocking the bourgeoisie may call attention to the artist the way a child’s shrieks call attention to the child, but such behavior does not inspire desire for a repeat performance.

When de Kooning framed toast and Cage called it art, did anyone ask if it is good art? Is framing a bread crumb great art, fascinating, instructive, transcendent? What kind of art is it and how does that framed toast compare to regular toast? How does that compare to the greatest art works our civilization has produced? Because if it is just a commonplace act, with no scholarship, mastery, or effort, then it is obviously not a work of art, there is no art to it.

Observation, seeing or hearing something, is not art; it is the act of perception. When Cage claims that silence reveals ambient sound as music, he made an assumption but he didn’t prove it; the reality test shows the opposite. There is always an audience for music but little audience for ambient noise in the city. No one has ever repeatedly listened to a recording of 4’33” the way they listen to their choices in music. John Cage actually proved that ambient sound is not music. He is a man of great talent but imperfection is the spice of genius.

Some of Cage’s assumptions prove to be failures only when they are presented as absolute statements. When express as questions, the answers are data leading to new ways of thinking about our auditory environment. If Cage restated his 4’33” piece as a question testing if ambient sound is music, there is no right or wrong answer, only observation and conclusion. Were Cage to ask if everything we do is music, he would reach valid conclusions proving or disproving that question. In such situations, we are still left with fascinating projects no matter what answers emerge. Either way, Cages acoustic works lead to expanded acoustic awareness and an advance in natural knowledge in art and in science.

Footnotes

1 Sol Lewitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Artm 1967, Artforum.

Sol Lewitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Artm 1967, Artforum.

https://www.artforum.com/features/paragraphs-on-conceptual-art-211354/

2  Larry Bloom, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, Wesleyan University Press, 2019

Larry Bloom, Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, Wesleyan University Press, 2019

3  Miklos Legrady, One Kilogram of nothing, artist;s website, 2025

Miklos Legrady, One Kilogram of nothing, artist;s website, 2025

https://legrady.com/

4  Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, The Disclosure Of The Agent In Speech And In Action p175\http://www.rainbow-season.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/action-Arendt-the_human_condition.pdf

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, The Disclosure Of The Agent In Speech And In Action p175\http://www.rainbow-season.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/action-Arendt-the_human_condition.pdf

5  Kyle Gann youtube channel https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Kyle+Gann

Kyle Gann youtube channel https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Kyle+Gann

6  Andrew Hamlin, Kyle Gann. No Such Thing As Silence: John Cage’s 4'33", music works, Yale University Press.2011

Andrew Hamlin, Kyle Gann. No Such Thing As Silence: John Cage’s 4'33", music works, Yale University Press.2011

https://www.musicworks.ca/reviews/books/kyle-gann-no-such-thing-silence-john-cage’s-433

7  In" Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", Benjamin writes that we see a painting alone; there was no way for the masses to organize and control themselves in their reception” as is possible when seeing a film in a group. The film is preferable to painting as the film is seen communally. This is important, as Benjamin tells us, because "all we can expect from art is an accurate representation of reality", and the only genuine art is that which is made by a committee of the working class to instruct the masses in Marxist doctrine." The reactionary attitude toward a Picasso painting changes into the progressive reaction toward a Chaplin movie.

In" Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", Benjamin writes that we see a painting alone; there was no way for the masses to organize and control themselves in their reception” as is possible when seeing a film in a group. The film is preferable to painting as the film is seen communally. This is important, as Benjamin tells us, because "all we can expect from art is an accurate representation of reality", and the only genuine art is that which is made by a committee of the working class to instruct the masses in Marxist doctrine." The reactionary attitude toward a Picasso painting changes into the progressive reaction toward a Chaplin movie.