art statement

Legrady bio

Legrady cv

Legrady's work

on the CCCA

Art Database

National Gallery

of Canada

collection

31works

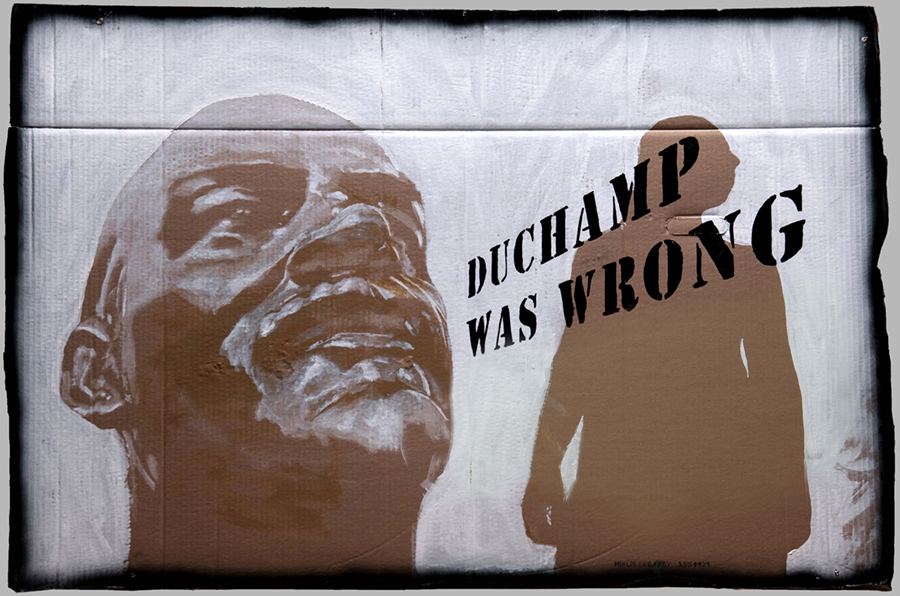

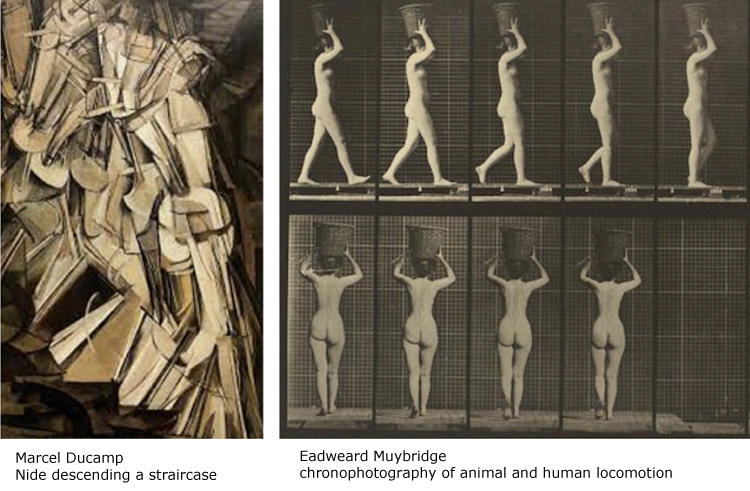

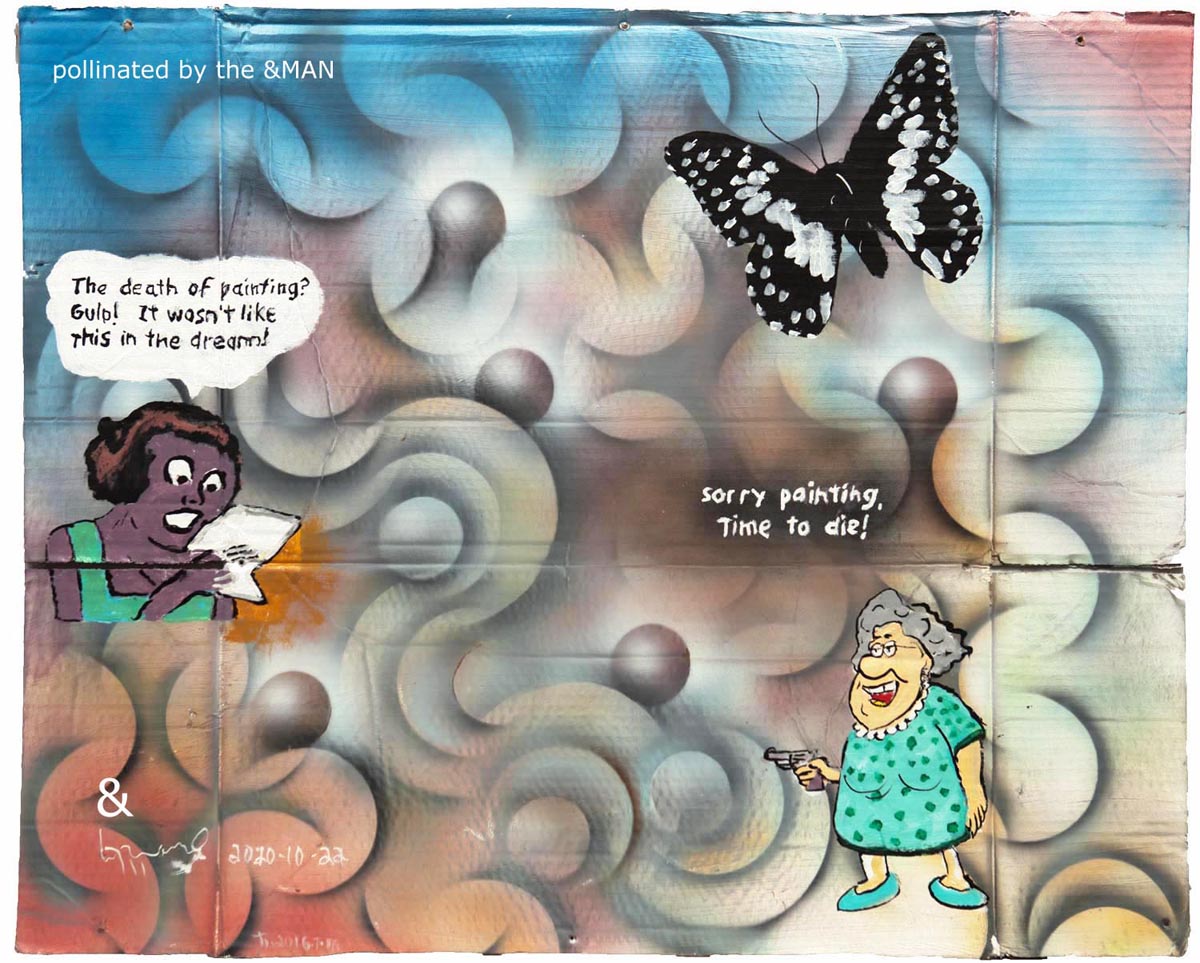

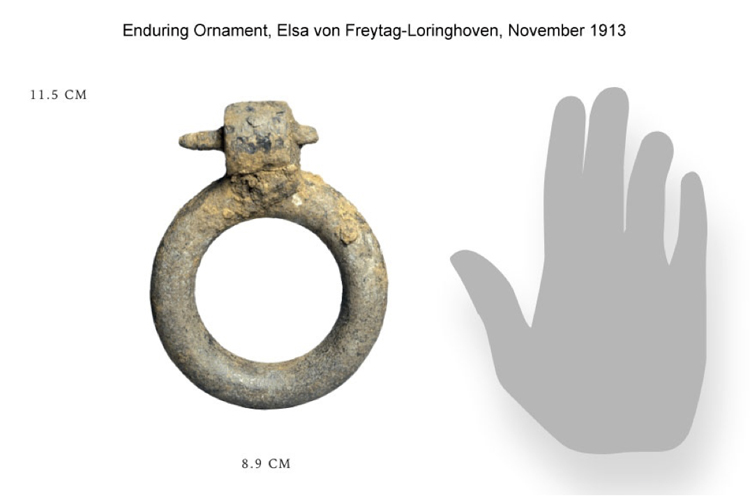

Painting © Miklos Legrady Destabilizing Marcel Duchamp we have the receipts The purpose of deconstruction is to locate hidden flaws, ambiguities, and paradoxes of which the author is probably unaware. Derrida’s method of deconstruction was to look past the irony and ambiguity to the layer that genuinely threatens to collapse that system, so we will follow that model here. Marcel Imagine if you repeatedly told everyone that you wanted to destroy art, that art was discredited and we should get rid of it, but nobody noticed... That would mean you were the famous artist Marcel Duchamp. Everybody knows that Marcel Duchamp had a deep, deep understanding of art. Everybody knows this, except the very few scholars who actually studied Marcel Duchamp and realized, much to their horror, that Duchamp presented very little understanding of art, if any. No one who does would say the things Duchamp said throughout his life. What did Marcel Duchamp say? There’s a 1968 youtube video shot a year before he died, Joan Bake well interviews Marcel Duchamp for BBC’s Late Night Line Up series, where Duchamp talks about after his early career, after the Large Glass, when he stopped painting, and he decided that art was not important to culture, art was discredited, and we should get rid of art the way some people got rid of religion. (1) As a scholar writing at the intersection of art and politics, for 15 years I studied Marcel Duchamp’s role in contemporary art, and now must warn the reader the answers are challenging to the point of discomfort. Marshall McLuhan pointed out that, much to his dismay, art had become anything you could get away with. While that sounds exciting, political science says your culture is your future. What if your future is anything that others can get away with? You don’t have to like it but you cannot deny it; for 75 years, facts slipped through the cracks. The most intelligent scholars and critics ignored the evidence staring them in the face in order to avoid conflict.(2) Duchamp was an international star and no one saw any benefit in alienating themselves by stirring up controversy, when so many others had built careers on the status quo. In spite of great art produced in the last century, more recent art history has often been a train wreck, starting with the moment when Picabia wrote in the DADA Manifesto that art was the opiate of idiots(3) and Duchamp seriously advised we get rid of art., Such were typical DADA tactics to shock the bourgeoisie and destabilize the art world. We were sold on the exciting idea of rebelling against tradition. Duchamp, Donald Judd, John Cage, and Thierry de Duve (Kant after Duchamp) all said that art cannot and should not be defined; art is anything an artist chooses to call by that name. Of course what cannot be defined cannot be seen; it fades into the background like tears lost in the rain. If art was anything an artist chose to call by that name, such irresponsible license would corrupt both artists and art world alike. We would be at the mercy of scammers and charlatans. Marcel Duchamp was an intelligent man but he lacked intelligence. To be intelligent is to have the mental acuity, while intelligence consists of relevant information. With accurate intelligence, we are capable of great achievement but Duchamp lacked the right stuff. He said painting was dead after he decided it was superficial. He did not know that painting is a non-verbal visual language. The science was not available in his formative years and by the time it was, Duchamp was deeply committed to a DADA strategy of discrediting painting, eventually rejecting all art. He said painting was dead but painting lives on. Painting is a visual language whose notation differs from writing, which started when calligraphy split off from pictography. The science of linguistics tells us that painting cannot die anymore than literature. Today, the science of linguistics says the long awaited death of painting is an unrealistic expectation. Painting is a non-verbal language, a system of notations much like literature, but operating on a different bandwidth. Painting and literature are not likely to die, they’ve been around since the dawn of history. We must assume that painting will not roll over and play dead, just because Duchamp wants to shock the bourgeoisie. Duchamp's Brand Duchamp’s brand was that of a French intellectual with a deep understanding of art, whereas he may have lost that understanding once he committed to DADA. That is the only objective conclusion we can come to on viewing the evidence in these pages. We must repeat that in a 1968 BBC interview, he said that art was an unnecessary obsession, art is discredited, and we should get rid of it the way some got rid of religion. (4) Both his language and art projects thereafter aimed to support this view No one who understands art would say such things. And so we must inquire who was Duchamp? Why did he say such things?, And why did the artworld adopt his views without any awareness of the contradictions in his argument to discredit art? This paper also considers why Duchamp remained an artist while maintaining throughout his life that his profession was discredited. We look at the psychology of denying one’s process and the consequences, that crippled his ability as an artist. much to his own disappointment. We are also concerned about an art world where Duchamp was a major influence. Schools still teach his ideas that render artists impotent. What does this mean for our social development, when your culture is your future? Who was Marcel Duchamp? Born into an upper middle class family where his brothers and sisters were artists, Duchamp (28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968) had shown remarkable talent for painting that found its apogee when he was 25 and painted Nude Descending a Staircase (1912). It was a work that referenced Eadward Muybridge’s(5) pioneering photographic studies of animal locomotion, made between 1878 and 1886. Before its first presentation at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants in Paris, it was rejected by the Cubists as being too Futurist. It was then exhibited with the Cubists at Galeries Dalmau's Exposició d'Art Cubista, in Barcelona, 20 April–10 May 1912.(6) “Nude Descending a Staircase” had it’s greatest success at the New York Armory show of 1913. Duchamp’s patron Arensberg could have placed him with any major gallery in New York but Duchamp did not like to work. Donald Kuspit wrote of Matisse out-performing him(7)  Was Marcel jealous of his painting’s fame when he complained of his own obscurity? It is possible his resentment was partly why he tried to kill painting, may be responsible for his claim that painting was dead. Painting was also hard work while shocking the bourgeoisie was an easier path to press attention, easier than “painting morning, noon, and night”. Robert Motherwell wrote“Duchamp was the great saboteur, the relentless enemy of painterly painting… His disdain for sensual painting was… intense.”(10) That Duchamp disliked painting so passionately already shows a disturbed personality. Shakespeare did not hate poetry. Baryshnikov did not hate dance, When Pierre Cabane asked where his anti-retinal attitude comes from, and Duchamp’s reply is nonsense, as painting is a visual language, although he did not know that. “From too great importance given to the retina. Since Courbet, it’s been believed that painting is addressed to the retina. That was everyone’s error… still interested in painting in the retinal sense. Before, painting had other functions: it could be religious, philosophical, moral… It’s absolutely ridiculous. It has to change; it hasn’t always been like this.” Duchamp wanted painting to be an illustration of intellectual ideas instead of a visual language that expresses what cannot be said in words. That took too much effort and he didn’t like effort, working morning, noon, and night. “In a period like ours, when you cannot continue to do oil painting, which after four or five hundred years of existence, has no reason to go on eternally… The painting is no longer a decoration to be hung in the dining room or living room. Art is taking on more the form of a sign, if you wish; it’s no longer reduced to a decoration”.(11) . On Pierre Cabane asking if easel painting is dead Duchamp replies “it’s dead for the moment, and for a good hundred and fifty years. Unless it comes back; one doesn’t know why, as there’s no good reason for it”. Duchamp had declared painting dead with his last oil on canvas, Tu m’ from 1918. (12)  ©Painting Miklos Legrady That said, the long awaited ‘death of painting’ is an unrealistic expectation. The science of nonverbal discourse dates back to Charles Darwin’s 1872 publication on the expression of emotions in humans and animals. Since then, scientists have repeatedly weighed in on non-verbal communication in art. Kevin Zeng Hu at MIT Media Lab writes “we all know how unwieldy texting can be and how much context can be lost, especially emotional context. Once you make it visual, you have a higher bandwidth to convey nuance.”(13) Science confirms that painting cannot die anymore than literature; both offer different kinds of notation in use even before the dawn of history. Duchamp claimed art was discredited yet remained an artist most of his life. Then he lost his inspiration as a result of his disrespect for the field. "It was like a broken leg", he told Jasper Johns...." I didn't mean to do it", and he quit art to play chess, which requires calculation but no creativity.. No one who understands art, or cares about art, would say such things as “I don’t believe in the creative function of the artist. He’s a man like any other… those who make things on a canvas, with a frame, they’re called artists. Formerly they were called craftsmen, a term I prefer.(14) Does Duchamp believe that Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were skilled interior decorators? We may also consider the influence of his friend Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, a title that may refer to Found Objects since Duchamp's Readymades predate Benjamin's famous article. Marxism also denies the creative power of artists. As Duchamp writes “I don’t believe in the creative function of the artist," so Benjamin wrote "The art of the proletariat after its assumption of power… or the art of a classless society… brush aside a number of outmoded concepts, such as creativity and genius, eternal value and mystery." For Duchamp, it is as if he said “I don’t believe in the medical skills of a doctor or the musical skills of a singer”. He rejected the notion that some have a superior insight. According to him, our notion that Duchamp had a superior insight is mistaken. He had instead a charisma that led others to adopt his views without consideration, with as little understanding of Duchamp’s words as Duchamp’s seeming understanding of art. Found Objects With his dislike of painting, Duchamp had painted himself into a corner. He admits he did not fully understand the readymades either. "The curious thing about the readymade is that I've never been able to arrive at a definition or explanation that fully satisfies me."(15) To this scholar it seems rather obvious that readymades are a perfect tool to discredit art, requiring neither vision nor talent, only the ability to bend over and pick up a discarded object. The bourgeoisie will surely be shocked to find traditions broken, and may even condescend to admire a urinal that tells us art is to piss on. Thus we discredit art. Somehow this implies that cultural workers have no taste. That which lacks taste is bland, but we will dive deeper into that conversation a little later. Duchamp only made a total of 13 readymades over a period of 30 years(16) When asked how he came to choose the readymade, Duchamp replied,“Please note that I didn’t want to make a work of art out of it ... when I put a bicycle wheel on a stool ... it was just a distraction.”(17) Duchamp’s refusal to have readymades treated as works of art led him to claim that “for a period of thirty years nobody talked about them and neither did I.”(18) . Francis Naumann In further consideration of Found Objects, Francis Naumann is the canonical Duchamp scholar who was also Duchamp’s confidant, and biographer. He wrote extensively on Duchamp over decades. I emailed him asking simply “what if the Bicycle Wheel is n Duchamp resisted certain interpretations of his readymades, particularly from those who claimed they contained aesthetic features comparable to those of traditional sculpture, having forgotten that industrial objects do have a designer, and the aesthetic of form following function. . “I threw the bottle rack and the urinal into their faces as a challenge,” he told Hans Richter in 1962, “and now they [the Neo-Dadaists] admire them for their aesthetic beauty.” In June of 1968, however, in the last televised interview before his death, Duchamp came to accept the fact that a viewer acquires a natural taste for objects seen over a prolonged period. “After twenty years, or forty years of looking at it,” he said of his Bottle Rack, “you begin to like it… That’s the fate of everything, you see?”(19) Naumann concludes this paragraph with his own words; "It was probably while admiring its aesthetic qualities that he wondered, to paraphrase his words, “if one could make a work of art out of materials that were not customarily associated with art”. This is proof, Naumann wrote, that the Bicycle Wheel is a work of art. I informed Mr. Naumann that no, Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven Moses came down from the mountain and found his people worshipping a golden urinal. Duchamp’s urinal (called Fountain), was most likely the product of a syphilitic madwoman who died in an insane asylum. Her name was Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (née Else Hildegard Plötz, 12 July 1874 – 14 December 1927). The urinal was signed 'R. Mutt 1917', and to a German 'R. Mutt' suggests Armut, meaning poverty; Elsa was poor Working class Elsa Plötz had embarked on a number of marriages and affairs, often with gay or impotent men. A marriage to Baron Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven gave her a title, although the Baron was penniless and worked as a busboy in New York. . Elsa was regularly arrested and incarcerated for offences such as petty theft or public nudity... Many remarked on her pungent body odor. She had certainly inspired Duchamp. “Around this time the baroness met, and became somewhat obsessed with the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp. ( A classic attraction of opposites, as Duchamp’s strict French discipline contrasted with Elsa’s total lack of that quality). One of her spontaneous pieces of performance art saw her taking an article about Duchamp's painting Nude Descending a Staircase and rubbing it over every inch of her naked body, connecting the famous image of the Nude with herself. She then recited a poem that climaxed with the declaration ‘Marcel, Marcel, I love you like Hell, Marcel.’ Duchamp politely declined her unwashed sexual advances. He was not a tactile man, and did not like to be touched. Being a Dadaist, he did recognize the originality of her anti-establishment rebellious art. He once said, 'The Baroness] is not a futurist. She is the future.'”(21) Years after her death, Duchamp appropriated the urinal without crediting Elsa, except for one letter to his sister. The incriminating evidence was later published by Duchamp’s biographer, Francis Naumann. “April II [1917] My dear Suzanne- impossible d’écrire. (in the Parisian French of 1917, this meant ‘nothing much to write about’, re Dr. Glynn Thompson.) - I heard from Crotti that you were working hard. Tell me what you are making and if it’s not too difficult to send. Perhaps, I could have a show of your work in the month of October or November-next-here. But tell me what you are making- Tell this detail to the family: The Independents have opened here with immense success. One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture it was not at all indecent-no reason for refusing it. The committee has decided to refuse to show this thing. I have handed in my resignation and it will be a bit of gossip of some value in New York- I would like to have a special exhibition of the people who were refused at the Independents-but that would be a redundancy! And the urinal would have been lonely- See you soon, Affect. Marcel.(22) Some pundits were not aware of Duchamp’s letter and took advantage of their position to write fallacious versions of the Fountain’s provenance. Sir Alistair MacFarlane is a former Vice-President of the Royal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor of Heriot-Watt University. Sir Alistair wrote in 2015 that “On 17 April, 1917 Duchamp discovered an ideal exhibit when strolling along Fifth Avenue in the company of Walter Arensberg, his patron, a collector, and Joseph Stella, a fellow artist. When they passed the retail outlet of J.L. Mott, Duchamp was fascinated by a display of sanitary ware. He had found what he had been diligently seeking; and persuaded Arensberg to purchase a standard, flat-backed white porcelain urinal. Taking it to his studio, he placed it on its back, signed it with the pseudonym ‘R. Mutt’, and gave it the nameFountain”.(23) MacFarlane dates his version a week after Duchamp’s letter to his sister. There’s no mention of Elsa. I emailed Sir Alistair asking for clarification; his publisher replied that Sir Alistair’s health is not good, we may not hear from him. MacFarlane’s source may have been an article by Will Gompertz(BBC's arts editor and previously director of Tate Media), who three years earlier had written a similar fabrication. “Meanwhile, in New York City, three well-dressed, youngish men had emerged from a smart duplex apartment at 33 West 67th Street and were heading out into the city. They were oblivious,,, to the fact that their afternoon stroll would also have epoch-making consequences on a global scale. Art was about to change for ever. The three made their way south until they reached 118 Fifth Avenue, the retail premises of JL Mott Iron Works, a plumbing specialist. Inside, Arensberg and Stella chatted, while their friend ferreted around among the bathrooms and door handles that were on display. After a few minutes he called the store assistant over and pointed to an unexceptional, flat-backed, white porcelain urinal. A Bedfordshire, the young lad said. The Frenchman nodded, Stella raised an eyebrow, and Arensberg, with an exuberant slap on the assistant's back, said he'd buy it… Duchamp took the urinal back to his studio, laid it down on its back and rotated it 180 degrees. He then signed and dated it in black paint on the left-hand side of its outer rim, using the pseudonym R Mutt 1917. His work was nearly done. There was only one job remaining: he needed to give his urinal a name. He chose Fountain. What had been, just a few hours before, a nondescript, ubiquitous urinal was now, by dint of Duchamp's actions, a work of art. At least it was in Duchamp's mind. He believed he had invented a new form of sculpture: one where an artist could select any pre-existing mass-produced object with no obvious aesthetic merit, and by freeing it from its functional purpose – in other words making it useless – and by giving it a name and changing its context, turn it into a de facto artwork. He called this new form of art a readymade: a sculpture that was already made. His intention was to enter Fountain into the 1917 Independents Exhibition, the largest show of modern art that had ever been mounted in the US.”(24) Of course logic tells us no “stuffy American art crowd” would ever visit the Independent show, which consistent of “rejected” avant garde art. . BBC's arts editor and previously director of Tate Media Will Gompertz’s description of the Fountain’s provenance sounds like a schoolboy’s fantasy, and of course it is a bare faced fabrication, if Duchamp’s letter to his sister is true. Dr. Glynn Thompson of Leeds University and Rutgers’s Stephanie Crawford question Will Gompertz’s tale as a fabrication; the Mott factory didn’t make a urinal similar enough to the one in the 1917 Alfred Stieglitz photographs.(25) <  Elsa’s first found object was a curtain ring she called “Enduring Ornament” that she used as a wedding ring in New York in1913,(26) the same year as Duchamp made his Bicycle Wheel in Paris, two years before he came to New York. Another sculpture named “God” adds credibility to her authorship of Fountain; one work insults religion while the other insults art. It is plausible Duchamp appropriated the urinal in 1951 when he started showing readymades as “non art”, 24 years after Elsa’s suicide. Scholars currently argue for and against this provenance. But Enduring Ornament, the sculpture she called God, and Duchamp’s letter to his sister seem to weigh in on Elsa’s side.  Picabia’s exploding cubist paintings looked insane compared to classical art; Duchamp’s The Large Glass was cracked and broken; so why shouldn’t a poor mad woman take a plumbing pipe and make a sculpture of it that she call God? And since she lived around artists, many of whom were Communists or at least liberal, they weren’t about to completely reject poor Elsa. Many artists were poor. Many were also insane; psychology says we’re all somewhere on the spectrum, so we may well hesitate when judging others. Marriages, passion, chess Duchamp also dreaded marriage, children, bourgeois servitude to social expectations; “It wasn’t necessary to encumber one’s life with too much weight, with too many things to do, with what is called a wife and children, a country house, an automobile. And I understood this, fortunately, rather early. This allowed me to live for a long time as a bachelor.”(27) Duchamp’s first marriage in 1927, lasted six months; “because I saw that marriage was as boring as anything, I was really much more of a bachelor than I thought. So, after six months, my wife very kindly agreed to a divorce … That’s it. The family that forces you to abandon your real ideas, to swap them for the things family believes in, society and all that paraphernalia.” He spoke of “a negation of woman in the social sense of the word, of the woman-wife, the mother, the children, etc. I carefully avoided all that, until I was sixty-seven. Then (1954) I married a woman (Alexina Teeny Sattler) who, because of her age, couldn’t have children.” Both were avid chess players.(28) The tale of Duchamp’s first marriage tells that in 1927 Marcel Duchamp married a young heiress called Lydie Sarazin-Lavassor. The honeymoon did not go well; the artist’s close friend Man Ray recalls that “Duchamp spent the one week they lived together studying chess problems and his bride, in desperation, got up one night when he was asleep and glued the chess pieces to the board.” They were divorced soon after,(29) Duchamp was obviously open minded about sexuality in his response to Frank Lloyd Wright’s question, posed to him at the Western Round Table on Modern Art in 1949. Wright,“You would say that this movement which we call modern art and painting has been greatly in debt to homosexualism [sic]?” Duchamp replied:“I believe that the homosexual public has shown more interest for modern art than the heterosexual public.”(30) A curious answer with a wink to Arensberg and his friends? Duchamp may or may not have been ambisexual but he queered the arts creatively and personally. Alex Robertson Textor attests that Duchamp “posed for Man Ray in drag, displaying exaggerated feminine mannerisms, though not passing particularly well as a woman”. Considered from a range of feminist perspectives, Duchamp’s tendency to see Rose Sélavy as his ‘muse’ represents an assimilation of an abstract ‘feminine’ as a territory for the critically transgressive. But since he was openly disdainful of feminism, this move is clearly problematic.”(31) The inevitable reality of taste There is a common thread of Marxism among artists in this time, expressed in a belief in the virtues of denying the individual. Duchamp told Pierre Cabane that his choice of readymades is always based on visual indifference, and, at the same time, on the total absence of good and bad taste. It was a genuine attempt at a nihilism that would bring a great revelation by discarding the self, but such revelation never came. For him, taste was a repetition of something already accepted.(32)In fact, taste is the result of hard won experience. When Duchamp tried to discard taste he may have meant bourgeois taste, but he tossed the baby with the bath water, he went too far. For a creative person who does not run with the lemmings, who has independent thoughts, taste is who you are; taste is all you got. By denying personal taste Duchamp was denying the individual, since taste distinguishes one individual from another. Ideas should make sense so as not to discredit the speaker. In an interview with Katherine Kuh, Duchamp said “I consider taste- bad or good - the greatest enemy of art”.(33) Elsewhere he states “I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my own tastes.(34) My intention was to] completely eliminate the existence of taste, bad or good or indifferent”.(35) To unpack that we describe taste; sweet and sour, bitter and salt; our taste comes in many flavors, colours, shapes, in style and song; taste is an instinctive judgment expressing our intelligence and our identity through personal choice. Without taste we have no choice, without choice we have no art. Taste is who you are; taste is all you got. In eliminating his own taste and by contradicting himself()< Duchamp compromised himself by discarding his own uniqueness. Of course there are inconsistencies to Duchamp’s thoughts. For example, if taste is the enemy of art, and Duchamp wanted to discredit art, should he or shouldn’t he follow his own taste, which consisted of contradicting his taste, in order to avoid it? This is likely another Gordian knot that stumped Duchamp. His repudiation of art was a marketing strategy that turned around and bit the biter. Rejecting art in favor of a vague Marxism Former Vice-President of the British Royal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor,Sir Alistair MacFarlane writes “before Marcel Duchamp, a work of art was an artifact, a physical object. After Duchamp it was an idea, a concept… Duchamp had two strategic objectives. First, to destroy the hegemony exerted by an establishment that claimed the right to decide what was, and what was not, to be deemed a work of art. Second, to puncture the pretentious claims of those who called themselves artists and in doing so assumed that they possessed extraordinary skills and unique gifts of discrimination and taste.” William Coopley’s obituary of Duchamp reads “he entered immortality at the time he left the easel and took art with him into creative life.”(36) Both MacFarlane and Coopley’s statements display a ridiculous failure of intelligence and logic. With all respect to Sir MacFarlane those claims to extraordinary skills were not pretentious; artists are professionals with a mastery of their field, so they do possess exceptional ability, discrimination and taste; that’s what it means to be a professional artist compared to an accountant or scientist with their own skill set. Duchamp obviously did not “take art with him into creative life” when he stopped painting. He left art on the easel when his mistaken assumptions rendered him impotent by destroying his motivation, after he convinced himself art was useless. He entered immortality for six decades only to be cast out on the seventh; he did not destroy the foundations of art, he destroyed his own creative ability. Rejecting the artist in favor of the concept And now history whispers that Plato reproached Pericles because he did not "make the citizen better" and because the Athenians were even worse at the end of his career than before.(Gorgias 515) Kristin Lee Dufour's school assignment at Oxford explains this radical philosophy: “The pertinence of the artist is erased in favor of the pertinence of the concept. In Duchamp’s readymades, the involvement of the artist as a generative source is minimal ... Thus, the value of the artist as a craftsman mastering a particular media is annihilated, as are values attached to any of these media.”(37) . Of course mastery lacks value to these young revolutionaries who can afford Oxford tuition fees and who hire craftsmen or women to do their homework. We forget all found objects were designed by someone, spotlighting the intellectual weakness of Dufour’s argument. Nor had she understood that Duchamp had tried to get rid of personal taste in art and failed. Peter Bürger goes even further than Kristin Lee Dufour, referencing Walter Benjamin: “the central distinction between the art of ‘bourgeois autonomy’ and the avant-garde is that whereas bourgeois production is ‘the act of an individual genius,’ the avant-garde responds with the radical negation of the category of individual creation ... all claims to individual creativity are to be mocked ... it radically questions the very principle of art in bourgeois society according to which the individual is considered the creator of the work of art.”( 38 When Bürger radically questions bourgeois society, he is actually signalling his own virtue in pointing to the horror when an artist is considered the creator of a work of art. Bürger fails to explain what these horrors are, other than the fury of an impotent armchair warrior. Now consider Edward Fry’s statement, published in 1972, that Hans Haacke “may be even more subversive than Duchamp, since he handles his readymades in such a way that they remain systems that represent themselves and thus do not let themselves assimilate with art.”(39) What is the point of this subversion? We should question instead the self-loathing that sees art as odious. Such undifferentiated practice is the realm of Thanatos, daemon of non-violent death. His touch is gentle, likened to that of his twin brother Hypnos (Sleep). The degradation of contemporary art In 2014 art historian and critic Barbara Rose wrote of Duchamp “I was angry he convinced so many that painting was dead, since above all, I loved painting. I got over this moment of pique because I was intrigued by his imagination and inventiveness. What Duchamp himself had done was always interesting and provocative. What was done in his name, on the other hand, was responsible for some of the silliest, most inane, most vulgar non-art still being produced by ignorant and lazy artists whose thinking stops with the idea of putting a found object in a museum.”(40) And yet such inane art was exactly what Duchamp wanted as part of his strategy to discredit art.(41) Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? is a Latin phrase found in the work of the Roman poet Juvenal from his Satires (Satire VI, lines 447, 8). It is literally translated as “Who will guard the guardians?” Duchamp’s inevitable collapse When he said art was discredited he probably didn’t mean it at first, it was a DADA tactic didactic. He obviously could not have been too invested in that statement, since he remained an artist for decades. Those words would come back to haunt him though, as they were likely the reason he lost his motivation and stopped making art. You can only profess an idea for so long before you begin to consider that it might be true: perhaps art was meaningless and unnecessary. This is likely the psychology that blocked Duchamp. In the Cabane interview, Jasper Johns wrote how Duchamp wanted to kill art (for himself, Johns added), so Marcel was likely the first victim of his own success. It looks like Duchamp at first did not really want to trash art, he only wanted to say that he did, and he needed the art world to be there to listen. Then over time, he went full Monty, believed his own press that art was discredited, and reaped the consequences. He threw art under the bus, in doing that he denied his own validity as an artist by denying art, which means he hit a wall, painted himself into a corner, suffered an artist’s block. To his own dismay, he lost his motivation to do what he said was worthless; he could not make art anymore. He’d done it; he’d gotten rid of art (for himself). Say something long enough and they will believe it; even you will believe it. He stopped making art. Jasper Johns went on to say Duchamp tolerated, even encouraged the mythology around that ‘stopping’, “but it was not like that …” He spoke of breaking a leg. “You didn’t mean to do it”(42) He lost his footing after he threw art under the bus. When he said art was discredited, he might have asked himself if it was true, but he didn’t and it killed his career. He still poked and prodded at Étant donné for twenty long years in a room behind his now empty studio. But obviously the muse was gone, and like any spurned lover she wasn’t coming back. In 2004, hundreds of British art experts agreed that Fountain was the most influential work of 20th century art.( ) Considering the semiotic implications, it is worrisome that scatology is so influential.. Those who think that art is to piss on should now leave the field to others with higher values. Waiting for Godot Duchamp gave up art once he lost interest and spent his last 20 years playing chess. He toured art communities as an art star playing chess in front of an art audience, and was paid a hefty artist’s fee. Many said such events deeply touched them and made them feel part of art history. These chess games were documented; they are occasionally recreated as a performance at some university, where two artists slowly repeat the 1960s chess moves in front of an art audience. What a lack of audacity, what a lack of creativity! The comparison to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot cannot be overestimated.  ©Painting Miklos Legrady Running with the lemmings. We ask what happened to the art world, whoagreed with nonsense and lauded their demise with breathless anticipation? Perhaps we have not seen as far as others because giants were standing on our shoulders. Or perhaps the artist's move from the Cedar Tavern to the Seminar Room is to blame., Artists no longer made a living from creating and selling art, but by teaching. The need to conform led to the silence of the lambs. When DADA said art was anything Duchamp could get away with, MAGA replied that politics was anything Trump could get away with. The art world created a fertile ground for Donald Trump, because your culture is your future. FOOTNOTE 1  1968 BBC interview with Marcel Duchamp where Duchamp says we should get rid of art. 1968 BBC interview with Marcel Duchamp where Duchamp says we should get rid of art. https://youtu.be/Zo3qoyVk0GU?si=bYdw47iUJ7CsWK8h 2  Curator Francesca Seravalle left out the part aboove section, writing that curating should awaken a collectigve memory, which suggests Dochamp saying we should gget rid of art does not fullfil that expectation and so should be ignored.. Curator Francesca Seravalle left out the part aboove section, writing that curating should awaken a collectigve memory, which suggests Dochamp saying we should gget rid of art does not fullfil that expectation and so should be ignored..https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbK-GPH-ATs 3  Francis Picabia - Dada Manifesto (1920) - 391.org Francis Picabia - Dada Manifesto (1920) - 391.orghttps://391.org/manifestos/1920-dada-manifesto-francis-picabia. 4  Joan Bakewell in conversation with Marcel Duchamp, Late Night Line-Up, BBC ARTS, 1968. Joan Bakewell in conversation with Marcel Duchamp, Late Night Line-Up, BBC ARTS, 1968.https://youtu.be/Zo3qoyVk0GU 5  Museum of Modern Art, Eadward Muybridge https://www.moma.org/artists/4192 Museum of Modern Art, Eadward Muybridge https://www.moma.org/artists/4192ftn6"> 6  Roger Allard, Sur quelques peintre, Les Marches du Sud-Ouest, June 1911, Roger Allard, Sur quelques peintre, Les Marches du Sud-Ouest, June 1911, pp. 57-64. In Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, A Cubism Reader, Documents and Criticism, 1906-1914, The University of Chicago Press, 2008 7  Francis M. Naumann and Donald Kuspit, Duchamp: An Exchange, Artnet Francis M. Naumann and Donald Kuspit, Duchamp: An Exchange, Artnet http://www.artnet.com/magazine/FEATURES/naumann/naumann6-15-11.asp 8  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, I live the life of a waiter, p95, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, I live the life of a waiter, p95, Da Capo Press. 9  ditto p45 ditto p4510  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Introduction, Robert Motherwell, p12, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Introduction, Robert Motherwell, p12, Da Capo Press.11  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A Window Into Something Else, p43, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A Window Into Something Else, p43, Da Capo Press. Ibid, p35. Ibid, p35.13  Lorraine Boissoneault, A Brief History of the GIF, Smithsonian Institue Magazine, 2017, Lorraine Boissoneault, A Brief History of the GIF, Smithsonian Institue Magazine, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/brief-history-gif-early-internet-innovation -ubiquitous-relic-180963543/ 14  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Eight Years of Swimming Lessons, p16, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Eight Years of Swimming Lessons, p16, Da Capo Press.15  Calvin Tomkins: Duchamp: A Biography, page 159. Holt Paperbacks Calvin Tomkins: Duchamp: A Biography, page 159. Holt Paperbackshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/readymades_of_Marcel_Duchamp 16  Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, Dada Readymades Kjan Academy Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, Dada Readymades Kjan Academyhttps://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/dada-and-surrealism/dada2/a/dada-readymades ftn17"> 17  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A window into something else, p48, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A window into something else, p48, Da Capo Press.ftn18"> 18  Marcel Duchamp Talking about readymades, Interview by Phillipe Collins. p.40, Hatje Cantz, N.Y./L.A. Marcel Duchamp Talking about readymades, Interview by Phillipe Collins. p.40, Hatje Cantz, N.Y./L.A.19  Francis Naumann, Chapter 112, The Recurrent, Haunting Ghost: Essays on the Art, Life and Legacy of Marcel Duchamp, Francis Naumann, Chapter 112, The Recurrent, Haunting Ghost: Essays on the Art, Life and Legacy of Marcel Duchamp, Readymade Press, 2012. https://legrady.com/writing/naumann.pdf 20  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A window into something else, p48, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A window into something else, p48, Da Capo Press.21  René Steinke, My Heart Belongs to DADA, New York Times, Aug. 18, 2002 René Steinke, My Heart Belongs to DADA, New York Times, Aug. 18, 2002https://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/18/magazine/my-heart-belongs-to-dada.html 22  Stephanie Crawford Richard Mutt, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Stephanie Crawford Richard Mutt, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University https://sinclairnj.blogs.rutgers.edu/2018/07/richard-mutt/ 23  Sir Alistair MacFarlane, Marcel Duchamp )1887-1968), Brief Lives, Philosophy Now, 2015 Sir Alistair MacFarlane, Marcel Duchamp )1887-1968), Brief Lives, Philosophy Now, 2015https://philosophynow.org/issues/108/Marcel_Duchamp_1887-1968 24  Will Gompertz, Putting modern art on the map, The Guardian, 2012 Will Gompertz, Putting modern art on the map, The Guardian, 201225  Irene Gammel, Baroness Elsa, Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity—A Cultural Biography Irene Gammel, Baroness Elsa, Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity—A Cultural BiographyMIT Press, ISBN:9780262572156 https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/baroness-elsa 26  Reed Enger, “Enduring Ornament,” inObelisk Art History, Published August 03, 2017; last modified August 29, 2019 Reed Enger, “Enduring Ornament,” inObelisk Art History, Published August 03, 2017; last modified August 29, 2019http://arthistoryproject.com/artists/elsa-von-freytag-loringhoven/enduring-ornament/ 27  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p76, Da Capo Press Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p76, Da Capo Press 28  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p76, Da Capo Press Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p76, Da Capo Press 29  The Oxford Dictionary of art, ed. Ian Chilvers, Marcel Duchamp, p221, Oxford University Press The Oxford Dictionary of art, ed. Ian Chilvers, Marcel Duchamp, p221, Oxford University Press 30  Douglas MacAgy, ed., "The Western Round Table on Modern Art" Douglas MacAgy, ed., "The Western Round Table on Modern Art"in Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt’s Modern Artists in America 31  Alex Robertson Textor, Encyclopaedia of Gay Histories and Cultures, p262, Garland Publishing, Inc. 2000 Alex Robertson Textor, Encyclopaedia of Gay Histories and Cultures, p262, Garland Publishing, Inc. 200032  Pierre Cabane Dialofue with Marcel Duchamp. p.48 Pierre Cabane Dialofue with Marcel Duchamp. p.4833  Katherine Kuh()< The Artist’s Voice, p92, Harper and Row, N.Y. 1960 Katherine Kuh()< The Artist’s Voice, p92, Harper and Row, N.Y. 196034  Duchamp quoted by Harriet & Sidney Janis in 'Marchel Duchamp: Anti-Artist' in Duchamp quoted by Harriet & Sidney Janis in 'Marchel Duchamp: Anti-Artist' in View magazine 3/21/45; reprinted in Robert Motherwell, Dada Painters and Poets (1951) 35  Irving Sandler, The New York school – the painters & sculptors of the fifties, Harper & Row, 1978, p. 164 Irving Sandler, The New York school – the painters & sculptors of the fifties, Harper & Row, 1978, p. 16436  Sir Alistair MacFarlane, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) Philosophy Now- June-July 2015 Sir Alistair MacFarlane, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) Philosophy Now- June-July 2015https://philosophynow.org/issues/108/Marcel_Duchamp_1887-1968 37  Kristin Lee Dufour. The Influence of Marcel Duchamp upon The Aesthetics of Modern Art, p3 12/2010, Kristin Lee Dufour. The Influence of Marcel Duchamp upon The Aesthetics of Modern Art, p3 12/2010,http://agence5970.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/LLMA_Dufour_Assignment2.pdf 38  Marjorie Perloff, Peter Bürger Theory of the Avant-Garde (1980, trans. 1984) Marjorie Perloff, Peter Bürger Theory of the Avant-Garde (1980, trans. 1984)https://web.stanford.edu/group/SHR/7-1/html/body_perloff.html#01 39  Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art, Iconoclasm and Vandalism, p278, Reaktion Books. Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art, Iconoclasm and Vandalism, p278, Reaktion Books.40  Barbara Rose, Rethinking Duchamp, The Brooklyn Rail, 2014. Barbara Rose, Rethinking Duchamp, The Brooklyn Rail, 2014. https://brooklynrail.org/2014/12/art/rethinking-duchamp 41  Joan Bakewell in conversation with Marcel Duchamp, Late Night Line-Up, BBC ARTS, 1968. Joan Bakewell in conversation with Marcel Duchamp, Late Night Line-Up, BBC ARTS, 1968.https://youtu.be/Zo3qoyVk0GU 42  Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press. Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press.43  Candy Light, How a Urinal Became the Most Influential Artwork of the 20th Century Candy Light, How a Urinal Became the Most Influential Artwork of the 20th Centuryhhttps://medium.com/@masterworksio/how-a-urina... |